News

Newswise — Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, Fondazione Santa Lucia IRCCS, and Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Rome have shown that pharmacological (drug) correction of the content of extracellular vesicles released within dystrophic muscles can restore their ability to regenerate muscle and prevent muscle scarring (fibrosis). The study, published in EMBO Reports, reveals a promising new therapeutic approach for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an incurable muscle-wasting condition, and has far-reaching implications for the field of regenerative medicine.

“Our study shows that extracellular vesicles are bioactive mediators that can transfer the benefits of medicine—in this case, HDAC inhibitors (HDACi)—to treat DMD,” says Pier Lorenzo Puri, M.D., professor in the Development, Aging and Regeneration Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys and co-corresponding author of the study. “We discovered the promise of this treatment almost 20 years ago and did all of the preclinical work, which led to a current clinical trial for boys with DMD. However, the therapeutic potential of HDACi has been so far limited by its systemic adverse effects.”

In the current clinical trial, boys with DMD are treated with HDACi at suboptimal doses due to the risk of adverse side effects. The scientists are hopeful that extracellular vesicles might provide a cell-free, non-immunogenic, transplantable tool for local delivery of bioactive particles that transfer HDACi to dystrophic muscles, thereby overcoming the undesirable secondary effects caused by chronic use at high doses.

“We believe this novel approach of using pharmacologically corrected extracellular vesicles may be used to safely deliver drugs such as HDACi directly to dystrophic muscles to obtain the beneficial action that would otherwise only be achieved at higher, toxic doses,” says Puri.

Extracellular vesicles are bioactive particles, meaning they have an effect in the body. They have recently attracted significant attention from the biomedical community because of their therapeutic potential. These particles contain information in the form of DNA, RNA or proteins and are exchanged from one cell to another. Alterations in the content of these particles leads to faulty communication between cells in dystrophic muscles and changes their behavior. In this study, the scientists discovered that these content alterations can be corrected to restore the physiological communication between the cells of dystrophic muscles.

Communication breakdown

Prior research from Puri’s team showed that as DMD progresses, special muscle-healing cells called fibro-adipogenic progenitors (FAPs) become corrupted and start to promote muscle wasting and fibrosis. The team suspected that altered communication between FAPs and muscle stem cells—perhaps via extracellular vesicles—might be part of the problem.

To answer this question, Martina Sandonà, Ph.D., first author of the study, and her colleagues conducted a series of experiments using muscle biopsies from boys with DMD who are enrolled in the clinical trial testing experimental HDACi treatment as well as a mouse model of DMD. The scientists were able to show that as DMD progresses, cellular communication via extracellular vesicles is progressively altered over time, which impairs the regeneration potential of DMD muscles. Importantly, the researchers demonstrated that correcting the content of the extracellular vesicles with an HDAC inhibitor activates muscle stem cells and promotes regeneration while reducing fibrosis and inflammation.

“Our findings can likely be extended to other conditions and diseases, as pharmacologically ‘lifted’ extracellular vesicles could be exploited as a general therapeutic tool in regenerative medicine,” says Valentina Saccone, Ph.D., group leader at Fondazione Santa Lucia IRCCS, tenured assistant professor at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore and co-corresponding author of the study. “These particles might also be used as an adjuvant approach for other treatments, such as gene or cell therapies.”

A ray of hope

Treatment advances can’t come soon enough for people with DMD and their loved ones. The genetic condition is caused by a lack of dystrophin, a protein that strengthens muscles, and causes progressive muscle degeneration. DMD primarily affects boys, with symptoms often appearing between the ages of 3 and 5. With recent medical advances, children with DMD now often survive beyond their teenage years into their early 30s, but effective treatments are still needed.

“For children and adults living with DMD and their families, research provides a ray of hope for a better future,” says Filippo Buccella, founder of Parent Project Italy, which has provided continual support to Puri’s team for the last 20 years. “This study uncovers a promising new therapeutic approach for DMD and brings us one step closer to treatments that may help children maintain muscle strength for as long as possible and live long, fulfilling lives.”

“The more options we have to treat DMD, the better, as it’s likely that drugs with different mechanisms of action could be more effective in combination,” says Sharon Hesterlee, Ph.D., executive vice president and chief research officer of the Muscular Dystrophy Association. “Dr. Puri’s work represents a unique approach that could prove complementary.”

A global team

The co-first authors of the study are Martina Sandonà of Fondazione Santa Lucia and Sapienza University of Rome; and Silvia Consalvi of Fondazione Santa Lucia. Additional study authors include Luca Tucciarone of Fondazione Santa Lucia and Sapienza University of Rome; Marco De Bardi and Daniela Francesca Angelini of Fondazione Santa Lucia; Manuel Scimeca of the University of Rome “Tor Vergata”; Valentina Buffa and Antonella Bongiovanni of the National Research Council of Italy; Adele D’Amico and Enrico Silvio Bertini of the Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital; Sara Cazzaniga of Paolo Bettica of Cinisello Balsamo; and Marina Bouché of Sapienza University of Rome.

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01AR076247-01, R01GM134712-01), Duchenne Parent Project Italy and Netherland, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, Epigen, Association Française contre les Myopathies, and the Italian Ministry of Health (GR2016-02362451). The study’s DOI is 10.15252/embr.202050863.

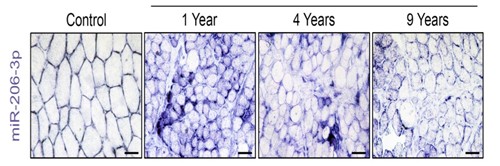

Photo Credit/Caption:

Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute

As Duchenne muscular dystrophy progresses, levels of a beneficial RNA (purple), called miR-206, in muscles decrease over time. In the study, the scientists were able to boost the amount of miR-206 in extracellular vesicles that are delivered to muscle stem cells, which promoted muscle repair.

Antibodies may not be body's primary defense against coronaviruses; T-cells can last decades

Newswise — More than 100 companies have rushed into vaccine development against COVID-19 as the U.S. government pushes for a vaccine rollout at "warp speed" -- possibly by the end of the year -- but the bar set for an effective, long-lasting vaccine is far too low and may prove dangerous, according to Marc Hellerstein of the University of California, Berkeley.

Most vaccine developers are shooting for a robust antibody response to neutralize the virus and are focusing on a single protein, called the spike protein, as the immunizing antigen. Yet, compelling evidence shows that both of these approaches are problematic, said Hellerstein, a UC Berkeley professor of nutritional sciences and toxicology.

A better strategy is to take a lesson from one of the world's best vaccines, the 82-year-old yellow fever vaccine, which stimulates a long-lasting, protective T-cell response. T-cells are immune cells that surveil the body continuously for decades, ready to react quickly if the yellow fever virus is detected again.

"We know what really good vaccines look like for viral infections," Hellerstein said. "While we are doing phase 2 trials, we need to look at the detailed response of T-cells, not just antibodies, and correlate these responses with who does well or not over the next several months. Then, I think, we will have a good sense of the laboratory features of vaccines that work. If we do that, we should be able to pick good ones."

Using a technique Hellerstein's laboratory developed and perfected over the past 20 years that assesses the lifespan of T-cells, it is now possible to tell within three or four months whether a specific vaccine will provide long-lasting cells and durable T-cell-mediated protection.

Hellerstein laid out his arguments in a review article published today in the journal Vaccine.

"There isn't a lot of room for major error here," Hellerstein said. "We can't just go headfirst down a less than optimal or even dangerous avenue. The last thing we want is for immunized people to get sick in a few months or a year, or get sicker than they would have. Whoever is paying for or approving the vaccine trials has the obligation to make sure that we look at the quality and durability of the T-cell response. And this would not delay the licensing process."

Misplaced focus on antibodies

Hellerstein points out that antibodies are not the primary protective response to infection by coronaviruses, the family of viruses that includes SARS-CoV-2. Indeed, high antibody levels to these viruses are associated with worse disease symptoms, and antibodies to coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, don't appear to last very long.

This was noted in people infected by the first SARS virus, SARS-CoV-1, in 2003. SARS patients who subsequently died had higher antibody levels during acute infection and worse clinical lung injury compared to SARS patients who went on to recover. In MERS, which is also a coronavirus infection, survivors with higher antibody levels experienced longer intensive care unit stays and required more ventilator support, compared to subjects with no detectable antibodies.

In contrast, strong T-cell levels in SARS and MERS patients correlated with better outcomes. The same has also played out, so far, in COVID-19 patients.

"A strong antibody response correlates with more severe clinical disease in COVID-19, while a strong T-cell response is correlated with less severe disease. And antibodies have been short-lived, compared to virus-reactive T-cells in recovered SARS patients," Hellerstein said.

The most worrisome part, he said, is that antibodies also can make subsequent infections worse, creating so-called antibody-dependent enhancement. Two vaccines -- one against a coronavirus in cats and another against dengue, a flavivirus that affects humans -- had to be withdrawn because the antibodies they induced caused potentially fatal reactions. If an antibody binds weakly against these viruses or falls to low levels, it can fail to "neutralize" the virus, but instead help it get into cells.

Antibody-dependent enhancement is well known in diseases such as dengue and Zika. A recent UC Berkeley study in Nicaragua showed that antibodies produced after infection with Zika can cause severe disease, including deadly hemorrhagic fever, in those later infected by dengue, a related viral disease. This dangerous cross-reaction may also occur with antibodies produced by a vaccine. Hellerstein noted that a robust T-cell response is key to maintaining high levels of antibodies and may prevent or counteract antibody-dependent enhancement.

T-cells are a long-lasting defense

Hellerstein primarily studies the dynamics of metabolic systems, tagging the body's proteins and cells with a non-radioactive isotope of hydrogen, deuterium and tracking them through the living body. He began to study the birth and death rates of T-cells in HIV/AIDS patients over 20 years ago, using sophisticated mass spectrometric techniques designed by his laboratory.

Then, three years ago, he teamed up with immunologist Rafi Ahmed and his colleagues at Emory University to determine how long T-cells induced by the yellow fever vaccine stick around in the blood. Surprisingly, he said, the same T-cells that were created to attack the yellow fever virus during the first few weeks after a live virus vaccination were still in the blood and reactive to the virus years later, revealing a remarkably long lifespan. He and the team estimated that the anti-yellow fever T-cells lasted at least 10 years and probably much longer, providing lasting protection from just one shot. Their long lifespan allows these cells to develop into a unique type of protective immune cell.

"They (the T-cells) are a kind of adult stem cell, sitting silently in very small numbers for years or decades, but when they see viral antigen they go wild -- divide like crazy, put out cytokines and do other things that help to neutralize the virus," he said. "They are like seasoned old soldiers resting quietly in the field, ready to explode into action at the first sign of trouble."

The same deuterium-labeling technique could be employed to measure the durability of a COVID-19 vaccine's T-cell response, helping to pinpoint the best vaccine candidates while trials are ongoing, he said.

"We can, in my view, tell you the quality and durability or longevity of your T-cell response within a few months," he said. "These tests can be used to judge vaccines: Is a candidate vaccine reproducing the benchmarks that we see in highly effective vaccines, like the ones against smallpox and yellow fever?"

Hellerstein said that he was motivated to write a review on the role of antibodies versus T-cells in protective immunity against SARS-Cov-2 when he heard from experts in vaccine development that companies would likely not be interested in testing anything beyond the antibody response. The reason given was that it would slow down the approval process or could even turn up problems with a vaccine.

"That is why I wrote this review, honestly, because I was so upset by this response," he said. "At this moment in history, how can we not want to know anything that might help us? We need to get beyond the narrow focus on antibodies and look at the breadth and durability of T-cells."

Worrisome focus on spike protein

Hellerstein was also alarmed that most vaccines under development are focusing exclusively on inducing an antibody response against only one protein, or antigen, in the COVID-19 virus: the spike protein, which sits on the surface of the virus and unlocks the door into cells. But important new studies have shown that natural infection by SARS-CoV-2 stimulates a broad T-cell response against several viral proteins, not just against the spike protein.

T-cells produced after natural infection in SARS patients are also very long-lived, he said. A recent study showed that patients who recovered from SARS-CoV-1 infection in 2003 produced CD4 and CD8 T-cells that are still present 17 years later. These T-cells also react to proteins in today's SARS-CoV-2, which the patients were never exposed to, indicating that T-cells are cross-reactive against different coronaviruses -- including coronaviruses that cause common colds.

These findings all call into question whether limiting a vaccine to one protein, rather than the complement of viral proteins that the body is exposed to in natural infection, will induce the same broad and long-lasting T-cell protection that is seen after natural infection.

In contrast, vaccines like the yellow fever vaccine that employ attenuated viruses -- viruses that divide, but are crippled and can't cause damage to the body -- tend to generate a robust, long-lasting and broad immune response.

"If you are going to approve a vaccine based on a laboratory marker, the key issue is, 'What is its relationship to protective immunity?' My view is that T-cells have correlated much better than antibodies with protective immunity against coronaviruses, including this coronavirus. And T- cells haven't shown a parallel in COVID-19 to antibody-dependent enhancement that could make things worse, not better," he said.

The effectiveness and durability of the first COVID-19 vaccines could impact, for years, the public's already questioning attitude toward vaccines, he warned.

"It would be a public health and 'trust-in-medicine' nightmare, with potential repercussions for years -- including a boost to anti-vaccine forces -- if immune protection wears off or antibody-dependent enhancement develops and we face recurrent threats from COVID-19 among the immunized," he wrote in his review article.

A new computer model developed by Stanford researchers could help policymakers choose the right reopening strategy.

Newswise — Pandemics bring pain. But so do the prescriptions for containing them: From school closures to total lockdowns, every government-mandated approach to blunting the impact of COVID-19 involves a trade-off between lives saved and jobs lost. Unfortunately, predicting the double-barreled economic and health effects of such policies has been difficult. Until now.

Stanford Graduate School of Business economists Mohammad Akbarpour and Shoshana Vasserman, together with Cody Cook, a PhD candidate at Stanford GSB, and colleagues at several other universities (see sidebar), have developed a computer model that can for the first time estimate the combined health and wealth outcomes of different policy responses to the coronavirus pandemic.

By computing the effects of different policies at different stages, the researchers were able to predict the impact of various reopening strategies on lives and livelihoods alike.

From Congestion Pricing to COVID-19

Prior to the emergence of COVID-19, Akbarpour and Vasserman were mulling the use of cellphone location data to study congestion pricing. When the pandemic erupted, Akbarpour and Vasserman suspected that the same data, which allows researchers to create computer-based populations of virtual people who move about and interact like real ones, could be used to model its spread.

They were right.

Using a combination of cellphone and demographic data provided by the transportation-planning startup Replica, the team constructed virtual versions of New York City, Sacramento, and Chicago and mapped the contacts between individuals as they did such things as going to work, attending school, and shopping for groceries.

By adding health, demographic, and occupational data drawn from electronic medical records and occupational surveys, the researchers were able to chunk the individuals in their virtual cities into hundreds of different types, such as 40-year-old men with diabetes who work in manufacturing, or 50-year-old women who work in technology and suffer from obesity, and so on.

They then calculated all of the contacts that each type of individual would have with the others on an average day and fed that information into an epidemiological model. The model predicted how many people would be sickened, quarantined, and killed as the coronavirus spread.

By imposing different policies (e.g., having everyone but essential workers stay home, requiring people to work remotely if possible), the researchers could alter the outcomes for each population. Because of the unique combination of health and occupational data they employed, they were able to estimate everything from the total number of hospitalizations and deaths to the total number of work days lost under each scenario.

Chicago Is Not Sacramento

In attempting to reopen their cities, officials have struggled to answer two basic questions: How do the health and economic outcomes of different reopening strategies compare? And do those outcomes vary from place to place?

“We wanted a data-driven way to address that,” Vasserman says.

There is a huge difference between what the same policy can do in Sacramento and what it can do in Chicago.

Mohammad Akbarpour

The model revealed that a so-called cautious reopening involving no formal restrictions on workplaces would lead to the greatest number of deaths but not to the lowest employment losses — presumably because even people who are totally free to work cannot do so if they are sick, quarantined, or dead.

Requiring people to work from home when possible, however, would greatly reduce the number of deaths while only marginally increasing the number of work days lost. So would requiring students and workers to come into school or work on alternate shifts or days.

But the impact of such policies varied widely from one city to another.

“There is a huge difference between what the same policy can do in Sacramento and what it can do in Chicago,” says Akbarpour.

For example, the model predicted that having people work remotely in Chicago would reduce deaths by 40 percent over a baseline return-to-normal scenario. But it would only reduce them by 20 percent in New York City, and hardly at all in Sacramento.

Even the impact of personal voluntary practices like masking and social distancing differed from city to city.

Overall, the model showed that masking was more effective at reducing deaths than any single government-mandated policy. But whereas masks only had to reduce infections by 10 percent to save more lives than a work-from-home policy in either New York City or Sacramento, they needed to reduce infections by at least 50 percent to achieve the same result in Chicago.

The team traced these disparities to a host of factors, with everything from the total number of contacts among individuals to the timing of the pandemic itself (i.e., whether a city was hit hard early on or spared until later) affecting local outcomes.

As a result, says Akbarpour, while the general recommendations remain largely the same, local prescriptions will vary.

Next Steps

The team is currently adding data on race and income to their model to explore the unequal impact that policies can have on different demographic groups.

They also plan to compare the consequences of shutting down specific kinds of businesses (e.g., restaurants versus nail salons) and to evaluate the spillover effect of suppressing entire sectors of the economy (i.e., what happens to coffee shop baristas if office workers all work from home?).

And they recently launched a website that allows users to compare the potential economic and health impacts of various policy mixes on a growing list of simulated cities. (They now have Replica data for Kansas City and are hoping to expand further.)

“The hope is that policymakers will use this to explore what could happen,” Vasserman says. “But if they really want to make decisions, they should put in the time and resources to get something tailor-made to their situation.”

https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/mapping-good-bad-pandemic-related-restrictions

Photo credit/caption:

Reuters/Brian Snyder

The research team mapped the contacts between individuals as they did such things as going to work, attending school, and shopping for groceries.

Findings support use of county-level cell phone location data as tool to estimate future trends of the COVID-19 pandemic

Newswise — Cambridge, Mass. - In March 2020, federal officials declared the COVID-19 outbreak a national emergency. Around the same time, most states implemented stay-at-home advisories - to different degrees and at different times. Publicly available cell phone location data - anonymized at the county-level - showed marked reductions in cell phone activity at the workplace and at retail locations, as well as increased activity in residential areas. However, it was not known whether these data correlate with the spread of COVID-19 in a given region.

In a new study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers from Mount Auburn Hospital and the University of Pennsylvania analyzed anonymous, county-level cell phone location data, made publicly available via Google, and incidence of COVID-19 for more than 2,500 U.S. counties between January and May 2020. The researchers found that changes in cell phone activity in workplaces, transit stations, retail locations, and at places of residence were associated with COVID-19 incidence. The findings are among the first to demonstrate that cell phone location data can help public health officials better monitor adherence to stay-at-home advisories, as well as help identify areas at greatest risk for more rapid spread of COVID-19.

"This study demonstrates that anonymized cell phone location can help researchers and public health officials better predict the future trends in the COVID-19 pandemic," said corresponding author Shiv T. Sehra, MD, Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Mount Auburn Hospital. "To our knowledge, our study is among the first to evaluate the association of cell phone activity with the rate of growth in new cases of COVID-19, while considering regional confounding factors."

Sehra and colleagues, including senior author Joshua F. Baker, MD, MSCE, of the University of Pennsylvania, incorporated publicly available cell phone location data and daily reported cases of COVID-19 per capita in majority of U.S. counties (made available by Johns Hopkins University), and adjusted the data for multiple county- and state- level characteristics including population density, obesity rates, state spending on health care, and many more. Next, the researchers looked at the change in cell phone use in six categories of places over time: workplace, retail locations, transit stations, grocery stores, parks and residences.

The location data showed marked reductions in cell phone activity in public places with an increase in activity in residences even before stay-at-home advisories were rolled out. The data also showed an increase in workplace and retail location activity as time passed after stay-at-home advisories were implemented, suggesting waning adherence to the orders over time, information that may potentially be useful at a public health level.

The study showed that urban counties with higher populations and a higher density of cases saw a larger relative decline in activity outside place of residence and a greater increase in residential activity. Higher activity at the workplace, in transit stations and retail locations was associated with a higher increase in COVID-19 cases 5, 10, and 15 days later. For example, at 15 days, counties with the highest percentage of reduction in retail location cell phone activity -- reflecting greater adherence to stay-at-home advisories -- demonstrated 45.5 percent lower rate of growth of new cases, compared to counties with a lesser decline in retail location activity.

"Some of the factors affecting cell phone activity are quite intuitive," said Sehra, who is also an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. "But our analysis helps demonstrate the use of anonymous county-level cell phone location data as a way to better understand future trends of the pandemic. Also, we would like to stress that these results should not be used to predict the individual risk of disease at any of these locations."

Newswise — MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. (August 31, 2020)—Warning witnesses about the threat of misinformation—before or after an event—significantly reduces the negative impact of misinformation on memory, according to new research performed at Tufts University.

The study, published online today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS), revealed that warnings can protect memory from misleading information by influencing the reconstructive processes at the time of memory retrieval. The researchers also found that when making accurate “memory decisions” participants in the study who were warned about the threat of misinformation displayed increased content-specific neural activity in regions of the brain associated with the encoding of actual event details. Likewise, warnings reduced content-specific neural activity in brain regions associated with the encoding of misleading event details.

The authors said the findings could have important implications for improving the accuracy of everyday memory and eyewitness testimony as part of the legal system.

“Memory is notoriously fallible and susceptible to error but our results show that a simple alert about possible misinformation is an effective tool to help eyewitnesses think back to the actual experience—with accuracy,” said Ayanna Thomas, a psychology professor in the School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts, who is a co-author and co-principal investigator of the study. “We expect this work could enhance interview procedures and protocols, specifically within the U.S. criminal justice system, which would benefit as a public entity from low-cost interview practices to improve the accuracy of eyewitness reports.”

The study involved a total of 161 people who engaged in two experiments—one behavioral and one using neuroscientific methods—in which they watched a silent film depicting a crime and responded to a test of recognition memory. In the first experiment, participants listened to an audio narrative that described the crime which included consistent details, misleading details and neutral details. After the audio narrative, participants were given a final recognition memory test that assessed memory for the original witnessed event. Importantly, participants were randomly assigned into one of three warning groups: no warning, pre-warning and post-warning.

The results demonstrated that people who were warned about the inaccuracy of the retelling were less susceptible to the misinformation than people who were not warned. The researchers also found that there was little difference whether participants were warned before or after.

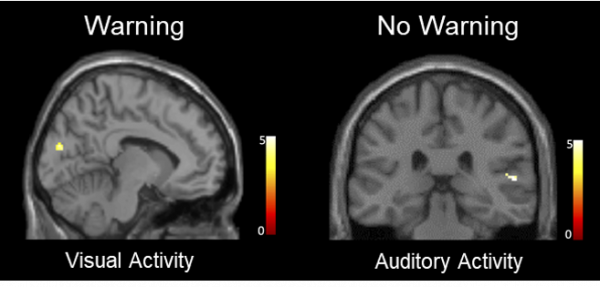

The second experiment involved a neuroimaging analysis designed to investigate the mechanisms by which warnings influence memory accuracy in the context of misinformation. In this evaluation, participants completed the identical tasks as they did in the first experiment but completed the final memory test while undergoing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The researchers found warnings not only increased reinstatement of visual activity associated with witnessing the actual crime but also decreased reinstatement of auditory activity associated with hearing misleading post-event information.

“This suggests that warnings increase memory accuracy by influencing whether we bring back to mind details from accurate or inaccurate sources of information,” said Elizabeth Race, a psychology professor at Tufts who also serves as a co-author and co-principal investigator of the study. Additionally, the strength of the content-specific cortical reactivation in visual and auditory regions predicted behavioral performance and the susceptibility of memory to misinformation.

“Together, these results provide novel insight into the nature of memory distortions due to misinformation and the mechanisms by which misinformation errors can be prevented,” said Jessica M. Karanian, first and corresponding author of the study, who was a postdoctoral fellow at Tufts while conducting the research and is now an assistant professor of psychology at Fairfield University. “The adoption of these interview practices by police departments might protect the integrity of eyewitness accounts and improve the likelihood of just outcomes for all involved.”

Past research on memory retrieval found that both prospective and retrospective warnings were able to mitigate the negative effect of misinformation on memory. However, this study not only affirms the beneficial effect of warning using a realistic scenario, such as testifying in a criminal case, but also demonstrates that prospective warnings can reduce misinformation errors in the context of repeated testing.

According to the Innocence Project, false eyewitness reports have contributed to approximately 70 percent of wrongful convictions. Despite efforts by the U.S. Department of Justice to create evidence-based standards in interview practices across police departments, the majority of surveyed police departments have not implemented such recommendations due to challenges in providing training and/or a lack of resources.

The researchers noted that since eyewitnesses are often interviewed and questioned multiple times throughout an investigation, a third party—such as a police office or an attorney—could provide a warning to an eyewitness that alerts them to the possibility of inaccuracies in post-event information that they might encounter in the future. The misinformation they might encounter could come from sources in the news, on social media or from a co-witness.

“We can envision the establishment of a new protocol for witness questioning in which witnesses are warned about the unreliability of subsequently-encountered information upon completing an initial interview,” said Karanian. “We could also imagine that such pre-warnings might be useful if provided at the beginning of some interviews that may include unverified information reported by co-witnesses.”

The research was a collaboration between Thomas’s Cognitive Aging and Memory Lab at Tufts University, which investigates interactions between memory and metamemory to better understand the important role metamemory plays in memory acquisition, distortion and access; and Race’s Integrative Cognitive Neuroscience Lab at Tufts, which uses a combination of cognitive neuroscience methods to answer questions about the neural mechanisms underlying human learning and memory.

Additional authors include Nat Rabb, a former research coordinator at the Cognitive Aging and Memory Lab at Tufts University; and Alia Wulff and McKinzey Torrance, who are both graduate students in the Department of Psychology at Tufts.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under grant No. 1728764. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Karanian, J.M., Rabb, N., Wulff, A., Torrance, M., Thomas, A.K., & Race, E. Protecting memory from misinformation: Warnings modulate cortical reinstatement during memory retrieval,” PNAS. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2008595117.

Photo:

Jessica M. Karanian/Fairfield University

Unwarned participants were more susceptible to misinformation and displayed greater auditory activity with heating the misinformation. Warned participants were less susceptible to misinformation and displayed greater visual activities associated with witnessing the original crime.

Newswise — WASHINGTON -- Misconceptions about the way climate and weather impact exposure and transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, create false confidence and have adversely shaped risk perceptions, say a team of Georgetown University researchers.

“Future scientific work on this politically-fraught topic needs a more careful approach,” write the scientists in a “Comment” published today in Nature Communications.

The authors include global change biologist Colin J. Carlson, PhD, an assistant professor at Georgetown’s Center for Global Health Science and Security; senior author Sadie Ryan, PhD, a medical geographer at the University of Florida; Georgetown disease ecologist Shweta Bansal, PhD; and Ana C. R. Gomez, a graduate student at UCLA.

The research team says current messaging on social media and elsewhere “obscures key nuances” of the science around COVID-19 and seasonality.

“Weather probably influences COVID-19 transmission, but not at a scale sufficient to outweigh the effects of lockdowns or re-openings in populations,” the authors write.

The authors strongly discourage policy be tailored to current understandings of the COVID-climate link, and suggest a few key points:

No human-settled area in the world is protected from COVID-19 transmission by virtue of weather, at any point in the year.

Many scientists expect COVID-19 to become seasonal in the long term, conditional on a significant level of immunity, but that condition may be unmet in some regions, depending on the success of outbreak containment.

All pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions are currently believed to have a stronger impact on transmission over space and time than any environmental driver.

“With current scientific data, COVID-19 interventions cannot currently be planned around seasonality,” the authors conclude.

Tweaking the adenovirus spike protein induces a more robust immune reaction for a cancer vaccine against gastric, pancreatic, esophageal and colon malignancies in animal models.

Newswise — PHILADELPHIA – Jefferson researchers developing a cancer vaccine to prevent recurrences of gastric, pancreatic, esophageal and colon cancers have added a component that would make the vaccine more effective. The change makes the vaccine less prone to being cleared by the immune system before it can generate immunity against the tumor components. The preclinical studies pave the way for a phase II clinical trial opening to patients this fall.

“Our data show strong immune responses in mice that might otherwise clear the vaccine, and suggests this approach will be more effective in the human trials we are starting shortly,” says Adam Snook, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics and researcher at the NCI-Designated Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center (SKCC)—Jefferson Health, a top ranked cancer center.

The research was published in Journal of ImmunoTherapy of Cancer on August 20, 2020.

Many vaccine targets, such as a tumor antigen or circulating virus, are introduced to the immune system through a “broker,” -- a safe negotiator of immunity. That broker introduces the vaccine components to the immune system, triggering a strong immune reaction needed for immunity, while protecting a person from the original threat – the cancer or disease-causing virus. Many vaccines, including some COVID-19 candidate vaccines, are often built using a strain of adenovirus as that broker or carrier.

Adenovirus is a common choice for vaccine development because of its safety profile and its generally strong and two-pronged immune reaction – both important characteristics for lasting immunity. But because adenoviruses also cause the common cold, many people have existing antibodies against the virus, and would clear away any adenovirus-based vaccine before it has a chance to act. New research from Dr. Snook’s laboratory shows that introducing a component of a less common adenovirus strain can make the vaccine more effective and less likely to be cleared by existing antibodies.

Rather than using a new carrier or broker, which would have triggered a restart in the clinical trials process, the investigators tweaked the existing vaccine based on commonly used serotype called adenovirus 5, or Ad5. To this, they added the spike protein of a rare adenovirus serotype Ad35 to create a hybrid vaccine Ad5.F35.

Dr. Snook and colleagues first showed that the Ad5.F35 cancer vaccine produced a comparable immune response to the original Ad5 vaccine in animal models of colorectal cancer. Similar to the Ad5, the vaccine with the F35 component added showed no toxicity in non-tumor tissue.

The researchers also showed that the Ad5.F35 vaccine was resistant to clearance by antibodies produced by mice exposed to Ad5. They also showed that the sera of colorectal cancer patients with Ad5 antibodies was not able to neutralize the vaccine.

“We speculate that based on these data, more than 90% of patients should produce a clinically meaningful immune response to the new version of the vaccine, whereas we would only expect about 50% to respond to the first version,” says Dr. Snook.

The phase II clinical trial aims to enroll 100 patients with gastric, pancreatic, esophageal or colon cancers who have been treated with first-line therapy and are in remission. Eligible patients will have undergone standard first-line therapy, usually surgery and chemo or radiation therapy, with no evidence of disease.

“This cancer vaccine is really designed to help the body keep the cancer from coming back,” says Babar Bashir, MD, assistance professor of medical oncology at Jefferson and researcher with the SKCC, who is the clinical leader on the trial. “It’s not powered to remove large tumor burden. But recurrence is a major problem for each of these cancers, and being able to reduce the chance of recurrence can translate to major improvements in a patient’s longevity.”

“This work is the latest advance in what is a larger effort at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson to develop effective cancer vaccines. We are so proud of the laboratory and clinical teams, who ensure that discoveries are fast-tracked to the clinic, and provide our patients in Philadelphia access to the most advanced form of cancer care,” said Karen E. Knudsen, PhD, EVP of Oncology Services at Jefferson Health and Enterprise Director of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center.

Article reference: John C. Flickinger Jr, Jagmohan Singh, Robert Carlson, Elinor Leong, Trevor R. Baybutt, Joshua Barton, Ellen Caparosa, Amanda Pattison, Jeffrey A. Rappaport, Jamin Roh, Tingting Zhan, Babar Bashir, Scott A. Waldman, and Adam E. Snook, “Chimeric Ad5.F35 vector evades anti-adenovirus serotype 5 neutralization opposing GUCY2C-targeted antitumor immunity,” Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer, DOI: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001046, 2020.

by Harvard Medical School

Newswise — More than a decade ago, electronic medical records were all the rage, promising to transform health care and help guide clinical decisions and public health response. With the arrival of COVID-19, researchers quickly realized that electronic medical records (EMRs) had not lived up to their full potential—largely due to widespread decentralization of records and clinical systems that cannot “talk” to one another.

Now, in an effort to circumvent these impediments, an international group of researchers has successfully created a centralized medical records repository that, in addition to rapid data collection, can perform data analysis and visualization. The platform, described Aug.19 in Nature Digital Medicine, contains data from 96 hospitals in five countries and has yielded intriguing, albeit preliminary, clinical clues about how the disease presents, evolves and affects different organ systems across different categories of patients COVID-19.

For now, the platform represents more of a proof-of-concept than a fully evolved tool, the research team cautions, adding that the initial observations enabled by the data raise more questions than they answer.

However, as data collection grows and more institutions begin to contribute such information, the utility of the platform will evolve accordingly, the team said.

“COVID-19 caught the world off guard and has exposed important deficiencies in our ability to use electronic medical records to glean telltale insights that could inform response during a shapeshifting pandemic,” said Isaac Kohane, senior author on the research and chair of the Department of Biomedical Informatics in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School. “The new platform we have created shows that we can, in fact, overcome some of these challenges and rapidly collect critical data that can help us confront the disease at the bedside and beyond.”

In its report, the Harvard Medical School-led multi-institutional research team provides insights from early analysis of records from 27,584 patients and 187,802 lab tests collected in the early days of epidemic, from Jan. 1 to April 11. The data came from 96 hospitals in the United States, France, Italy, Germany and Singapore, as part of the 4CE Consortium, an international research repository of electronic medical records used to inform studies of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our work demonstrates that hospital systems can organize quickly to collaborate across borders, languages and different coding systems,” said study first author Gabriel Brat, HMS assistant professor of surgery at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a member of the Department of Biomedical Informatics. “I hope that our ongoing efforts to generate insights about COVID-19 and improve treatment will encourage others from around the world to join in and share data.”

The new platform underscores the value of such agile analytics in the rapid generation of knowledge, particularly during a pandemic that places extra urgency on answering key questions, but such tools must also be approached with caution and be subject to scientific rigor, according to an accompanying editorial penned by leading experts in biomedical data science.

“The bar for this work needs to be set high, but we must also be able to move quickly. Examples such as the 4CE Collaborative show that both can be achieved,” writes Harlan Krumholz, senior author on the accompanying editorial and professor of medicine and cardiology and director of the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at Yale-New Haven Hospital. What kind of intel can EMRs provide? In a pandemic, particularly one involving a new pathogen, rapid assessment of clinical records can provide information not only about the rate of new infections and the prevalence of disease, but also about key clinical features that can portend good or bad outcomes, disease severity and the need for further testing or certain interventions.

These data can also yield clues about differences in disease course across various demographic groups and indicative fluctuations in biomarkers associated with the function of the heart, kidney, liver, immune system and more. Such insights are especially critical in the early weeks and months after a novel disease emerges and public health experts, physicians and policymakers are flying blind. Such data could prove critical later: Indicative patterns can tell researchers how to design clinical trials to better understand the underlying drivers that influence observed outcomes. For example, if records are showing consistent changes in the footprints of a protein that heralds aberrant blood clotting, the researchers can choose to focus their monitoring, treatments on organ systems whose dysfunction is associated with these abnormalities or focus on organs that could be damaged by clots, notably the brain, heart and lungs.

The analysis of the data collected in March demonstrates that it is possible to quickly create a clinical sketch of the disease that can later be filled in as more granular details emerge, the researchers said.

In the current study, researchers tracked the following data:

Total number of COVID-19 patients

Number of intensive care unit admissions and discharges

Seven-day average of new cases per 100,000 people by country

Daily death toll

Demographic breakdown of patients

Laboratory tests to assess cardiac, immune and kidney and liver function, measure red and white blood cell counts, inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, as well as two proteins related to blood clotting (D-dimer) and cardiac muscle injury (troponin)

Telltale patterns The report’s observations included:

Demographic analyses by country showed variations in the age of hospitalized patients, with Italy having the largest proportion of elderly patients (over 70 years) diagnosed with COVID-19.

At initial presentation to the hospital, patients showed remarkable consistency in lab tests measuring cardiac, immune, blood-clotting and kidney and liver function.

On day one of admission, most patients had relatively moderate disease as measured by lab tests, with initial tests showing moderate abnormalities but no indication of organ failure.

Major abnormalities were evident on day one of diagnosis for C-reactive protein—a measure of inflammation—and D-dimer protein, a chemical that measures blood clotting with test results progressively worsening in patients who went on to develop more severe disease or died.

Levels of the liver enzyme bilirubin, which indicate liver function, were initially normal across hospitals but worsened among persistently hospitalized patients, a finding suggesting that most patients did not have liver impairment on initial presentation.

Creatinine levels—which measure how well the kidneys are filtering waste—showed wide variations across hospitals, a finding that may reflect cross-country variations in testing, in the use of fluids to manage kidney function or differences in timing of patient presentation at various stages of the disease.

On average, white blood cell counts—a measure of immune response—were within normal ranges for most patients but showed elevations among those who had severe disease and remained hospitalized longer.

Even though the findings of the report are observations and cannot be used to draw conclusions, the trends they point to could provide a foundation for more focused and in-depth studies that get to the root of these observations, the team said.

“It’s clear that amid an emerging pathogen, uncertainty far outstrips knowledge,” Kohane said. “Our efforts establish a framework to monitor the trajectory of COVID-19 across different categories of patients and help us understand response to different clinical interventions.”

Co-investigators included Griffin Weber, Nils Gehlenborg, Paul Avillach, Nathan Palmer, Luca Chiovato, James Cimino, Lemuel Waitman, Gilbert Omenn, Alberto Malovini; Jason Moore, Brett Beaulieu-Jones; Valentina Tibollo; Shawn Murphy; Sehi L’Yi; Mark Keller; Riccardo Bellazzi; David Hanauer; Arnaud Serret-Larmande; Alba Gutierrez-Sacristan; John Holmes; Douglas Bell; Kenneth Mandl; Robert Follett; Jeffrey Klann; Douglas Murad; Luigia Scudeller; Mauro Bucalo; Katie Kirchoff; Jean Craig; Jihad Obeid; Vianney Jouhet; Romain Griffier; Sebastien Cossin; Bertrand Moal; Lav Patel; Antonio Bellasi; Hans Prokosch; Detlef Kraska; Piotr Sliz; Amelia Tan; Kee Yuan Ngiam; Alberto Zambelli; Danielle Mowery; Emily Schiver; Batsal Devkota; Robert Bradford; Mohamad Daniar; Christel Daniel; Vincent Benoit; Romain Bey; Nicolas Paris; Patricia Serre; Nina Orlova; Julien Dubiel; Martin Hilka; Anne Sophie Jannot; Stephane Breant; Judith Leblanc; Nicolas Griffon; Anita Burgun; Melodie Bernaux; Arnaud Sandrin; Elisa Salamanca; Sylvie Cormont; Thomas Ganslandt; Tobias Gradinger; Julien Champ; Martin Boeker; Patricia Martel; Loic Esteve; Alexandre Gramfort; Olivier Grisel; Damien Leprovost; Thomas Moreau; Gael Varoquaux; Jill-Jênn Vie; Demian Wassermann; Arthur Mensch; Charlotte Caucheteux; Christian Haverkamp; Guillaume Lemaitre; Silvano Bosari, Ian Krantz; Andrew South; Tianxi Cai.

Relevant disclosures: Co-authors Riccardo Bellazzi of the University of Pavia and Arthur Mensch, of PSL University, are shareholders in Biomeris, a biomedical data analysis company.

New York City – US Epicenter of First Surge in Hospitalized Covid-19 Patients – has Poor Average Hospital Nurse Staffing

Newswise — Philadelphia (August 18, 2020: 7:00 AM EST) – According to a new study published today in BMJ Quality & Safety, many hospitals in New York and Illinois were understaffed right before the first surge of critically ill Covid-19 patients. The study, “Chronic Hospital Nurse Understaffing Meets Covid-19,” documented staffing ratios that varied from 3 to 10 patients for each nurse on general adult medical and surgical units. ICU nurse staffing was better but also varied significantly across hospitals.

New York City, an international gateway to the US with three major international airports and the early epicenter of the Covid-19 surge in the US, had the poorest average hospital nurse staffing on the eve of the Covid-19 medical emergency.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that the workload had adverse consequences on nurses and on patient care. One third of patients in New York state and Illinois hospitals did not give their hospitals excellent ratings and would not definitely recommend their hospital to family and friends needing care.

“Half of nurses right before the Covid-19 emergency scored in the high burnout range due to high workloads, and one in five nurses said they planned to leave their jobs within a year,” said lead author Karen Lasater, PhD, RN, an assistant professor and researcher at the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research (CHOPR) at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (Penn Nursing). “It is an immense credit to nurses that in such an exhausted and depleted state before the pandemic they were able to reach deep within themselves to stay at the hospital bedside very long hours and save lives during the emergency,” continued Lasater.

“It is very important for the public to take note that in this large study of nurses practicing in New York and Illinois hospitals, half of nurses gave their hospitals unfavorable grades on patient safety and two-thirds would not definitely recommend their hospital to family and friends,” said CHOPR Director Linda Aiken, PhD, RN, a senior researcher and professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She noted that nurses have been rated in the Gallup poll as the profession most trusted by the American public for past 18 consecutive years.

The researchers surveyed all registered nurses (RNs) holding active licenses to practice in New York state and Illinois during the period December 16, 2019 to February 24, 2020, immediately prior to the Covid-19 medical emergency. Hospital nurses reported on the number of patients assigned to them to care for at one time. These nurse reports were linked to Medicare patient-reported outcomes for the same hospitals. They studied 254 hospitals throughout New York state and Illinois, including 47 hospitals in the metropolitan New York area (the five NYC boroughs plus Nassau and Westchester counties).

Policy debate on safe nurse staffing standards

Both New York state and Illinois have pending legislation requiring hospitals to meet minimum safe nurse staffing standards--no more than four patients per nurse on adult general medical and surgical units. The study found that most hospitals in both states currently do not meet these proposed standards, nor do they even meet the safe nurse staffing standard of five patients per nurse set by legislation in California 20 years ago.

“This study provides an important public service by documenting in real time and in states debating current nurse staffing legislation actual hospital nurse staffing levels—information not now easily accessible to the public—and the adverse consequences of such great variation in an essential component of hospital care—nursing,” said Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, coauthor and Chief Officer, Nursing Regulation at the National Council of State Boards of Nursing.

The study’s authors conclude:

there is no standardization in nurse staffing in NY and IL hospitals;

the majority of hospital nurses in these states were burned out and working in understaffed conditions immediately prior to the surge in critically ill Covid-19 patients;

understaffed hospitals pose a public health risk;

pending legislation in NY and IL may result in hospital staffing more aligned with the public’s interest;

the Nurse Licensure Compact also offers a solution and may ease the strain on hospitals.

More study findings…

Mean staffing in adult medical and surgical units in NY and IL hospitals varied from 3.36 patients-per-nurse to 9.7 patients per nurse and in ICUs from 1.5 to 4 patients per nurse.

Each additional patient per nurse significantly increased the proportion of both patients and nurses giving unfavorable hospital quality and safety ratings, after differences in hospital characteristics such as teaching status, size, and technology availability were taken into account.

Half of nurses were burned out, 31 percent were dissatisfied with their jobs, and 22 percent intended to leave their jobs within a year.

Half of nurses gave their hospitals an unfavorable grade on patient safety, a third gave unfavorable ratings on prevention of infections, and 70 percent would not definitely recommend the hospital where they worked to a family member or friend.

65 percent of nurses reported delays in care were common because of insufficient staff and 40 percent reported frequent delays in care due to missing supplies including medications and missing or broken equipment.

The study was carried out by the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing in partnership with the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Funding for the study was from the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, the National Institute of Nursing Research/NIH, and the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Photo Credit: Penn Nursing/Stock

Frontline Impact Project Works with Corporate Donors to Provide Food, Beverages, Personal Care Items, Wellness Products and Mental Health Services to Frontline Heroes

NEW YORK -- Amid a devastating Covid-19 resurgence, Frontline Impact Project is offering the nation’s healthcare and emergency response personnel access to donated snacks, meals, beverages, personal care items, mental health services, and accommodations. Created by The KIND Foundation, Frontline Impact Project has become a primary vehicle through which the business community has shown support for the men and women who are keeping America’s communities healthy. Frontline Impact Project is a streamlined and efficient way for institutions to request and receive resources and surface new needs as the pandemic evolves.

Institutions eligible for donations include hospitals, assisted living facilities, nursing homes, community healthcare centers, outpatient clinics, EMS squads. Frontline Impact Project serves institutions of all sizes throughout the country ─ from a town fire department with 20 firefighters to a multi-state hospital system employing thousands of workers.

Norman Stein, Chief Development Officer and Senior Vice President, Boston Medical Center, says, "It is of vital importance we provide our frontline caregivers with nourishment as they work tirelessly to care for our patients and community, and the donation from Frontline Impact Project has certainly helped us stay committed to that goal."

Sean Gibson, Manager, Duke University Hospital’s Trauma Center, echoed Stein’s sentiment saying, “We are grateful for Frontline Impact Project’s support of our healthcare community. We need everyone’s help to overcome this global health crisis, and donations such as this make a notable difference for our workers on the front lines.”

At www.frontlineimpact.org, representatives from frontline institutions can submit requests for resources along with a reference to validate the institution’s legitimacy. To ensure efficiency, departments or units within a larger institution are encouraged to work with their internal procurement team before requesting donations. After a request has been submitted, Frontline Impact Project matches the requester with a corporate donor(s). The donor(s) then work to deliver the product and/or service directly. While not every request is fulfilled, Frontline Impact Project does all it can to ensure needs are met.

To date, nearly 60 corporate partners, including KIND, Unilever, Extra Gum, Nestlé, Keurig Dr Pepper, Justin’s, Hint, Harry’s, RISE Brewing Co., Headspace and Image Skincare, have donated more than 3.4 million products. The platform has made 525 matches across 41 states.

“We are prepared to support the needs of frontline healthcare workers and first responders no matter how long it takes for this crisis to pass,” says Michael Johnston, President of The KIND Foundation. “Frontline workers’ needs will inevitably change in the days and weeks to come. Our intention is to recruit diverse partners now so that we are poised to meet new and unexpected needs later.”

Visit www.frontlineimpact.org for more information. Direct questions to Jonathan Yates at jyates@lubetzky.org.