News

Newswise — GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. —

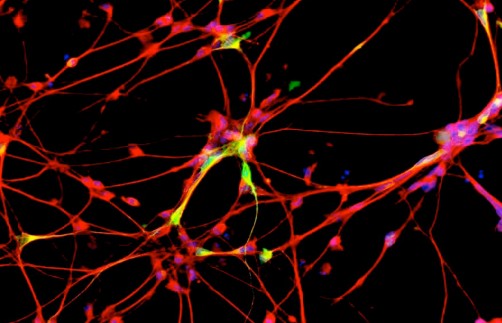

A new investigational drug originally developed for type 2 diabetes is being readied for human clinical trials in search of the world’s first treatment to impede the progression of Parkinson’s diseasefollowing publication of research findings today in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

“We hope this will be a watershed moment for millions of people living with Parkinson’s disease,” says Patrik Brundin, M.D., Ph.D., director of Van Andel Research Institute’s Center for Neurodegenerative Science, chairman of The Cure Parkinson’s Trust’s Linked Clinical Trials Committee, and the study’s senior author. “All of our research in Parkinson’s models suggests this drug could potentially slow the disease’s progression in people as well.”

Until now, Parkinson’s treatments have focused on symptom management. If successful in human trials, MSDC-0160 would be the world’s first therapy to treat the underlying disease and slow its progression—potentially improving quality of life and preventing the occurrence of falls and cognitive decline. It may also reduce or delay the need for medications that can have debilitating side effects, says Brundin.

Parkinson’s disease afflicts between 7-10 million people worldwide, including an estimated 1 million Americans, and these numbers are expected to increase dramatically as the average human lifespan increases. There is currently no cure, and first-line treatment has remained relatively unchanged since the introduction oflevodopa in the 1960s.

Tom Isaacs, a co-founder of The Cure Parkinson’s Trust who has lived with Parkinson’s for 22 years, says MSDC-0160 represents one of the most promising treatment the Trust’s international consortium has seen to date.

“Our scientific team has evaluated more than 120 potential treatments for Parkinson’s disease, and MSDC-0160 offers the genuine prospect of being a breakthrough that could make a significant and permanent impact on people’s lives in the near future,” says Isaacs. “We are working tirelessly to move this drug into human trials as quickly as possible in our pursuit of a cure.”

MSDC-0160 was developed by Kalamazoo, Michigan-based Metabolic Solutions Development Company (MSDC) to treat type 2 diabetes. In 2012, Brundin recognized it as an exciting drug candidate because of its mode of action, proven safety in people, local availability and the start-up company’s interest in collaborating on drug repurposing initiatives. After four years of work, the effects of the drug in the laboratory exceeded Brundin’s expectations.

The novelty of MSDC-0160 stems from a recently revived revelation that Parkinson’s may originate, at least partially, in the body’s energy metabolism. The new drug appears to regulate mitochondrial function in brain cells and restore the cells’ ability to convert basic nutrients into energy. Consequently, the cells’ ability to handle potentially harmful proteins is normalized, which leads to reduced inflammation and less nerve cell death.

“Parkinson’s disease and diabetes may have vastly different symptoms with unrelated patient outcomes; however, we’re discovering they share many underlying mechanisms at the molecular level and respond similarly to a new class of insulin sensitizers like MSDC-0160,” says Jerry Colca, Ph.D., co-founder, president and chief scientific officer of MSDC.

While Brundin says he is eager to see MSDC-0160 launched into a clinical trial in Parkinson’s disease, he’s equally excited about the possibility of testing the drug in Lewy body dementia and other cognitive decline conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

“This is an immensely promising avenue for drug discovery,” says Brundin. “Whatever the outcome of the upcoming trial for Parkinson’s, we now have a new road to follow in search of better treatments that cut to the root of this and other insidious diseases.”The Cure Parkinson’s Trust and Van Andel Research Institute are currently working with MSDC to address regulatory issues and obtain funding to organize the clinical trial, which Brundin hopes can begin sometime in 2017.

Funding for the research was provided by Van Andel Research Institute, The Cure Parkinson’s Trust, the Campbell Foundation, and the Spica Foundation.

The paper’s authors include Anamitra Ghosh, Trevor Tyson, Sonia George, Erin N. Hildebrandt, Jennifer A. Steiner, Zachary Madaj, Emily Schulz, Emily Machiela, Martha L. Escobar Galvis, Jeremy M. Van Raamsdonk and Patrik Brundin, all of Van Andel Research Institute; William G. McDonald and Jerry R. Colca, both of Metabolic Solutions Development Company; and Jeffrey H. Kordower, of Rush University Medical Center and Van Andel Research Institute.

# # #

Newswise —

Simon Fraser University researchers have found that high-resolution brain scans, coupled with computational analysis, could play a critical role in helping to detect concussions that conventional scans might miss.

In a study published in PLOS Computational Biology, Vasily Vakorin and Sam Doesburg show how magnetoencephalography (MEG), which maps interactions between regions of the brain, could detect greater levels of neural changes than typical clinical imaging tools such as MRI or CAT scans.

Qualified clinicians typically use those tools, along with other self-reporting measures such as headache or fatigue, to diagnose concussion. They also note that related conditions such as mild traumatic brain injury, often associated with football player collisions, don’t appear on conventional scans.

“Changes in communication between brain areas, as detected by MEG, allowed us to detect concussion from individual scans, in situations where MRI or CT failed,” says Vakorin. The researchers are scientists with the Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Institute based at SFU, and SFU’s ImageTech Lab, a new facility at Surrey Memorial Hospital. Its research-dedicated MEG and MRI scanners make the lab unique in western Canada.

The researchers took MEG scans of 41 men between 20-44 years of age. Half had been diagnosed with concussions within the past three months.

They found that concussions were associated with alterations in the interactions between different brain areas—in other words, there were observable changes in how areas of the brain communicate with one another.

The researchers say MEG offers an unprecedented combination of “excellent temporal and spatial resolution” for reading brain activity to better diagnose concussion where other methods fail.

Relationships between symptom severity and MEG-based classification also show that these methods may provide important measurements of changes in the brain during concussion recovery.

The researchers hope to refine their understanding of specific neural changes associated with concussions to further improve detection, treatment and recovery processes.

The research was funded by Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC).

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise —

Combination drug treatments have become successful at long-term control of HIV infection, but the goal of totally wiping out the virus and curing patients has so far been stymied by HIV's ability to hide out in cells and become dormant for long periods of time. Now a new study on HIV's close cousin, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), in macaques finds that a proposed curative strategy could backfire and make things worse if the virus is in fact lurking in the brain.

One of the proposed curative strategies for HIV, known as "shock and kill," first uses so-called latency-reversing agents to wake up dormant viruses in the body, making them vulnerable to the patient's immune system. The idea is that this, in combination with antiretroviral medicines, would wipe out the majority of infected cells.

But based on a study of macaques with SIV, a group of researchers warns in a report published in the January 2 issue of the journal AIDS that such a strategy could cause potentially harmful brain inflammation.

"The potential for the brain to harbor significant HIV reservoirs that could pose a danger if activated hasn't received much attention in the HIV eradication field," saysJanice Clements, Ph.D., professor of molecular and comparative pathobiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "Our study sounds a major cautionary note about the potential for unintended consequences of the shock-and-kill treatment strategy."

HIV research efforts have long focused on prevention and developing antiretroviral therapies that keep the virus in check without eradicating it, essentially transforming HIV into a manageable chronic condition, says Lucio Gama, Ph.D., assistant professor of molecular and comparative pathobiology at Johns Hopkins and the lead author of the new study. Then, in 2009, a group in Berlin reported it had cured a man of HIV by giving him a bone marrow transplant from a donor whose genetics conferred natural resistance to the virus. This galvanized federal funding of new research projects aimed at finding a more broadly applicable "AIDS cure," Gama says. He and Clements are part of that pursuit as members of the Collaboratory of AIDS Researchers for Eradication.

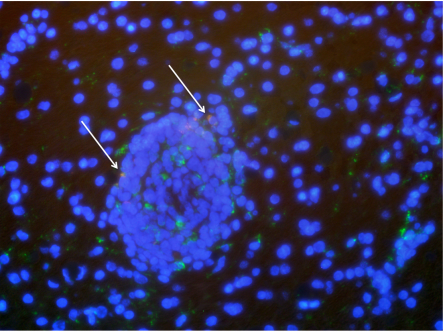

One cure strategy being pursued is to find a medication that would "wake up" virus in the reservoirs, forcing it to reveal itself. But Gama says that could be problematic if HIV reservoirs exist in the brain, and investigators already had some evidence that they do: the many cases of AIDS dementia that developed before the current antiretroviral cocktail treatment was developed. "Research had also shown that HIV can infect monocytes in the blood, which we know cross into the brain," he says. But no studies had definitively answered whether significant reservoirs of latent HIV in patients under long-term therapy could be sustained in the brain -- in part because, in autopsies, it is unclear whether virus detected in the brain comes from brain cells themselves or surrounding blood.

For the new study, Clements, Gama and their collaborators treated three pig-tailed macaque monkeys infected with SIV with antiretrovirals for more than a year. Then the researchers gave two of the macaques ingenol-B, a latency-reversing agents thought to "wake up" the virus. "We didn't really see any significant effect," Gama says, "So we coupled ingenol-B with another latency-reversing agent, vorinostat, which is used in some cancer treatments to make cancer cells more vulnerable to the immune system." The macaques also continued their course of antiretrovirals throughout the experiment.

After a 10-day course of the combined treatment, one of the macaques remained healthy, while the other developed symptoms of encephalitis, or brain inflammation, Gama says, and blood tests revealed an active SIV infection. When the animal's illness worsened, the researchers humanely killed it and carefully removed the blood from its body so that blood sources of the virus would not muddle their examination of the brain. Testing revealed SIV was still present in the brain, but only in one of the regions analyzed: the occipital cortex, which processes visual information. The affected area was so small that "we almost missed it," he says.

Gama cautions that the results of their study on macaques with SIV may not apply to humans with HIV. It's also possible, he says, that the encephalitis was transient and could have resolved by itself. Still, he says, the results signal a need for extra caution in exploring ways to flush out HIV reservoirs and eradicate the virus from the body.

Other authors on the paper are Celina M. Abreu, Erin N. Shirk, Sarah L. Price, Ming Li, Greg M. Laird, Kelly A. Metcalf Pate and Robert F. Siliciano of The Johns Hopkins University; Stephen W. Wietgrefe and Ashley T. Haase of the University of Minnesota; Shelby L. O'Connor of the University of Wisconsin; Luiz Pianowski of Kyolab in Brazil; Carine van Lint of the Université Libre de Bruxelles in Belgium; and the LRA-SIV Study Group.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number P01MH070306-01), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (grant number U19A1076113), the National Institutes of Health's Office of the Director (grant numbers P40OD013117 and P51OD011106), the Research Facilities Improvement Program (grant numbers RR15459-01 and RR020141-01), the France Recherche Nord & Sud Sida-HIV Hépatites, the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (FRS-FNRS Belgium), the Fondation Roi Baudouin, the NEAT program and the Wallo on Region (the Excellence Program Cibles).

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise — RIVERSIDE, Calif. (www.ucr.edu) —

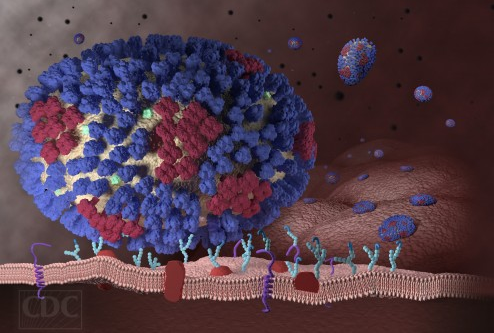

A team of researchers, co-led by a University of California, Riverside professor, has found a long-sought-after mechanism in human cells that creates immunity to influenza A virus, which causes annual seasonal epidemics and occasional pandemics.

The research, outlined in a paper published online today in the journal Nature Microbiology, could have broad implications on the immunological understanding of human diseases caused by RNA viruses including influenza, Ebola, West Nile, and Zika viruses.

“This opens up a new way to understand how humans respond to viral infections and develop new methods to control viral infections,” said Shou-Wei Ding, a professor of plant pathology and microbiology at UC Riverside, who is the co-corresponding author of the paper.

The findings build on more than 20 years of research by Ding on antiviral RNA interference (RNAi), which involves an organism producing small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to clear a virus.

His initial research showed that RNAi is a common antiviral defense in plants, insects and nematodes and that viral infections in these organisms require active suppression of RNAi by specific viral proteins. That work led him to study RNAi as an antiviral defense in mammals.

In a 2013 paper in the journal Science he outlined findings that show mice use RNAi to destroy viruses. But, it remained an open debate as to whether the same was true in humans.

That open debate led Ding back to a key 2004 paper in which he described a new activity of a protein (non-structural protein 1, or NS1) in the influenza virus that can block the antiviral function of RNAi in fruit flies, a common model system used by scientists.

In the current Nature Microbiology paper, the researchers demonstrated that human cells produce abundant siRNAs to target the influenza A virus when the viral NS1 is not active.

They showed that the creation of viral siRNAs in infected human cells is mediated by an enzyme known as Dicer and is potently suppressed by both the NS1 protein of influenza A virus and a protein (virion protein 35, or VP35) found in Ebola and Marburg viruses.

The researchers in the lab of the co-corresponding author, Kate L. Jeffrey, an investigator in the Massachusetts General Hospital gastrointestinal unit and an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, further demonstrated that the infections of mature mammal cells by influenza A virus and other RNA viruses are inhibited naturally by RNAi, using mice cells specifically defective in RNAi.

"Our studies show that the antiviral function of RNAi is conserved in mammals against distinct RNA viruses, suggesting an immediate need to assess the role of antiviral RNAi in human infectious diseases caused by RNA viruses, including Ebola, West Nile, and Zika viruses," Jeffrey said.

The Nature Microbiology paper is called “Induction and suppression of antiviral RNA interference by influenza A virus in mammalian cells.”

In addition to Ding, the authors are: Yang Li (UC Riverside and Fudan University in China); Jinfeng Lu, Shuwei Dong, Yanhong Han, Wan-Xiang Li, and Fedor V. Karginov (all of UC Riverside); Megha Basavappa, D. Alexander Cronkite, John T. Prior, Hans-Christian Reinecker and Sihem Cheloufi (all of Harvard Medical School and/or Massachusetts General Hospital); and Paul Hertzog (of Hudson Institute of Medical Research in Australia.)

Newswise — CHICAGO -

What if it was possible to prevent your child from getting eczema -- a costly, inflammatory skin disorder -- just by applying something as inexpensive as petroleum jelly every day for the first six months of his or her life?

A Northwestern Medicine study published today (Dec. 5) in JAMA Pediatrics found that seven common moisturizers would be cost effective in preventing eczema in high-risk newborns. By using the cheapest moisturizer in the study (petroleum jelly), the cost benefit for prophylactic moisturization was only $353 per quality-adjusted life year – a generic measure of disease burden that assesses the monetary value of medical interventions in one’s life.

$274The average amount of money families that are caring for a child with eczema spend per month on medical costs

Eczema impacts as many as 20 percent of children and costs the U.S. healthcare system as much as $3.8 billion dollars every year. Previous studies have shown that families caring for a child with the costly skin disorder can spend as much as 35 percent of their discretionary income – an average of $274 per month.

“It’s not only terrible for the kids, but also for their families,” said lead and corresponding study author Dr. Steve Xu, a resident physician in dermatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “Eczema can be devastating. Beyond the intractable itch, a higher risk of infections and sleep problems, a child with eczema means missed time from school, missed time from work for parents and huge out-of-pocket expenses. So if we can prevent that with a cheap moisturizer, we should be doing it.”

If we can prevent (eczema) with a cheap moisturizer, we should be doing it.”

Dr. Steve XuResident physician in dermatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Early studies from Japan, the U.S. and the U.K. have suggested that full-body application of moisturizers for six to eight months, beginning within the first few weeks of life, can reduce the risk that eczema will develops. Xu’s study took that one step further and examined the cost-effectiveness of seven common, over-the-counter moisturizer products, such as petroleum jelly, Aquaphor, Cetaphil and Aveeno.

“There’s an important economic argument to be made here,” Xu said. “Moisturizers are an important intervention dermatologists use to treat eczema. They play a big role in getting our patients better. But insurers do not usually cover the cost of moisturizers. We're arguing for their inclusion in health insurance coverage.”

Xu acknowledges the evidence is preliminary on prophylactic moisturization but said, “We’re not giving them an oral drug or injecting them with a medication; there is minimal risk. We’re putting Vaseline on these babies to potentially prevent a very devastating disease.”

In addition to preventing eczema, Xu cites emerging work that preserving the skin barrier may also reduce the risk of other health problems like food allergies. He notes that larger, long-term clinical studies are underway to see if prophylactic moisturizing leads to sustained benefits.

Newswise —

Doctors, pilots, air traffic controllers and bus drivers have at least one thing in common — if they're exhausted at work, they could be putting lives at risk. But the development of a new urine test, reported in the ACS journal Analytical Chemistry, could help monitor just how weary they are. The results could potentially reduce fatigue-related mistakes by allowing workers to recognize when they should take a break.

The effects of fatigue have long been recognized and studied as a problem in the transportation and healthcare industries. In the early 2000s, studies published in scientific journals reported that fatigue-related mistakes were linked to thousands of vehicular crashes every year, and were a major concern in patient safety. Weariness can cause anyone on or off the job to lose motivation and focus, and become drowsy. Although very common, these symptoms come with biochemical changes that are not well understood. Zhenling Chen, Xianfa Xu and colleagues set out to determine whether a urine test could detect these changes.

The researchers analyzed urine samples from dozens of air traffic controllers working in civil aviation before and after an 8-hour shift on the job. Out of the thousands of metabolites detected, the study identified three that could serve as indicators of fatigue. Further work is needed to validate what they found, the researchers say, but their initial results represent a new way to investigate and monitor fatigue — and help prevent worn-out workers from making potentially dangerous errors.

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Civil Aviation Administration of China.

Newswise — MANHATTAN, KANSAS —

Kansas State University researchers have discovered the secret ingredient to improving kitchen food safety: include hand-washing reminders and meat thermometer instructions in published recipes. Edgar Chambers IV, co-director of the university's Sensory Analysis Center, and collaborative food scientists have found that only 25 percent of people use a meat thermometer when they are cooking at home. But when a recipe includes a reminder, 85 percent of people will use a thermometer. The researchers saw similar results for hand-washing: Only 40 to 50 percent of people wash their hands when cooking, but 70 to 80 percent of people will wash their hands when a recipe reminds them. "This is such an easy thing to do: Just add the information to the recipe and people follow it," said Edgar Chambers, who is also a university distinguished professor of food, nutrition, dietetics and health. "It's a simple way to reduce foodborne illness and we can actually reduce health care costs by simply adding information to recipes. It's a great finding and a great piece of information for the promotion of food safety information." Chambers and his research team – including researchers at Tennessee State University and RTI International in North Carolina — have published the research in the Journal of Food Protection. They presented the results to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which intends to start including these food safety instructions in recipes that it develops, Chambers said. The four-year collaborative project is supported by a $2.5 million USDA grant. The researchers have spent three years studying consumer shopping and cooking behaviors. Now the researchers are spending the fourth and final year working with the Partnership for Food Safety Education in Washington, D.C., to develop a nationwide food safety campaign. The researchers want to educate consumers, manufacturers, grocers, journalists, magazines and publishers on the importance of including food safety instructions in published recipes. "We want to provide research-based information for consumers," Chambers said. "The goal is to promote safe behaviors so that people actually begin to do them every day in the kitchen and as part of their shopping behavior." The project focused on several areas of food safety with poultry and eggs, including using meat thermometers, washing hands frequently and storing meat in plastic bags provided by the grocery stores. The researchers observed 75 people cook two dishes — a Parmesan chicken breast and a turkey patty with mushroom sauce — following recipes that did not have food safety instructions. Another group of 75 participants cooked the same dishes following recipes that did include food safety instructions. The dishes required the participants to handle raw meat, eggs and fresh produce while scientists observed how often the participants washed their hands or used a meat thermometer. By comparing the two groups, the researchers found that 60 percent more people used a meat thermometer and 20 to 30 percent more people washed their hands when the recipes included reminders about the two food safety practices. "This is such a wonderful outcome," Chambers said. "It's such an easy thing to do and such an easy way to help people remember to be safe. It doesn't cost anything — just a little extra paper and a little extra time to wash your hands and use that thermometer." The researchers also are studying kitchen lighting, which also can affect food safety. Many people are switching to LED lights and energy-efficient lights for kitchens, which is great news for consumers, but bad news for food safety, Chambers said. The energy-efficient lights make meat and poultry appear as if they are more done than they actually are. "We have shown through research that changing to more modern lighting in kitchens makes people believe their meat patties are done sooner than they would be under old lighting, which is wrong," Chambers said. "That is not good news for consumers unless they are using a meat thermometer." The researchers recently published the lighting-related research in the Journal of Sensory Studies. The Sensory Analysis Center is an internationally recognized research institute that conducts consulting, education and consumer sensory research on a variety of products and topics.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise —

The study is the first to look closely at the effects of the Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi) program on people with health conditions that could be affecting their sleep. SHUTi aims to help people overcome their sleep problems by retraining them in healthy sleep behaviors. It is built on cognitive behavioral therapy, a widely used treatment for insomnia. Of the 303 people enrolled in the study, about half had either a medical or psychiatric condition.

Ultimately, approximately 70 percent of the SHUTi users had significant improvements, and more than half (56.6 percent) were in the "no insomnia" range one year after using SHUTi. In general, SHUTi proved significantly more effective than online sleep education information – the type of tips that might be found online – provided to a control group of study participants.

"We really tried to have as robust a study design as we possibly could to see if [SHUTi] would stand up over time," said University of Virginia School of Medicine Professor Lee Ritterband, PhD, one of the program's creators. "We found that those who got the SHUTi intervention did much better…and the main symptoms of insomnia were significantly improved and stayed improved over time."

Could Help 'Unimaginable Numbers'

Based on the study findings, the researchers have concluded that online programs without in-person human involvement can meaningfully improve sleep. The Internet, they say, "provides a less-expensive, scalable treatment option that could reach previously unimaginable numbers of people."

Overall, the study found that the benefits of SHUTi were similar to those found in trials of cognitive behavioral therapy delivered by healthcare providers. The measure of effectiveness was based on experiences self-reported by study participants rather than a measurement of time spent sleeping.

Newswise — Boston, Mass. —

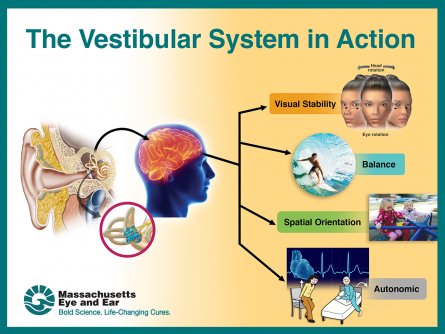

A new study led by researchers at Massachusetts Eye and Ear found that vestibular thresholds begin to double every 10 years above the age of 40, representing a decline in our ability to receive sensory information about motion, balance and spatial orientation. The report was published online ahead of print in Frontiers in Neurology.

“In our study, vestibular decline was clearly evident above the age of 40,” said senior author Daniel M. Merfeld, Ph.D. (at right in photo), Director of the Jenks Vestibular Physiology at Mass. Eye and Ear and a Professor of Otolaryngology at Harvard Medical School. “Increased thresholds correlate strongly with poorer balance test results, and we know from previous studies that those who have poorer balance have much higher odds of falling.”

More than half of the population will see a doctor at some point in their lives with symptoms related to the vestibular system (e.g., dizziness, vertigo, imbalance and blurred vision). The vestibular system, made up of tiny canals in the inner ear, is responsible for receiving information about motion, balance and spatial orientation.

With the goal of determining whether sex or age affected the function of the vestibular system, the researchers administered balance and motion tests to 105 healthy people ranging from 18 to 80 years old and measured their vestibular thresholds (“threshold” refers to the smallest possible motion administered that the subject is able to perceive correctly). While they found no difference between the thresholds of male and female subjects, they found that the thresholds increased above the age of 40 for all motions studied.

The researchers also found that these increasing thresholds strongly correlated with failure to complete a standardized test for balance. This correlation shows that fall risk is substantially impacted by vestibular function. Using data from previous studies, the researchers suggest that vestibular dysfunction could be responsible for as many as 152,000 American deaths each year. This estimate would place vestibular dysfunction third in the United States behind heart disease and cancer as a leading cause of death among Americans.

The correlation between vestibular thresholds and balance also suggests that there may be better ways to screen vestibular function and ways to develop therapies that may improve their thresholds.

“We’ve known for a long while that patients with vestibular disorders have disturbed balance,” said Dr. Merfeld. “If worse vestibular function leads to falls, perhaps we can develop balance aids or physical therapy exercises to improve balance or vestibular function and prevent those falls.”

Authors on the Frontiers in Neurology report include Dr. Merfeld, Maria Carolina Bermudez Rey, Tania Leeder and Yong Bian of the Jenks Vestibular Physiology Laboratory at Massachusetts Eye and Ear/Harvard Medical School; Torin K. Clark, of the Jenks Vestibular Physiology Laboratory at Mass. Eye and Ear/Harvard Medical School and the University of Colorado at Boulder; Wei Wong, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School. Research supported by NIH/NIDCD R01-DC01458 and R01-DC014924.

About Massachusetts Eye and EarMass. Eye and Ear clinicians and scientists are driven by a mission to find cures for blindness, deafness and diseases of the head and neck. Now united with Schepens Eye Research Institute, Mass. Eye and Ear is the world's largest vision and hearing research center, developing new treatments and cures through discovery and innovation. Mass. Eye and Ear is a Harvard Medical School teaching hospital and trains future medical leaders in ophthalmology and otolaryngology, through residency as well as clinical and research fellowships. Internationally acclaimed since its founding in 1824, Mass. Eye and Ear employs full-time, board-certified physicians who offer high-quality and affordable specialty care that ranges from the routine to the very complex. In the 2016–2017 “Best Hospitals Survey,” U.S. News & World Report ranked Mass. Eye and Ear #1 in the nation for ear, nose and throat care and #1 in the Northeast for eye care. For more information about life-changing care and research, or to learn how you can help, please visit MassEyeAndEar.org.

Newswise —

To "turn off" particular regions of genes or protect them from damage, DNA strands can wrap around small proteins, called histones, keeping out all but the most specialized molecular machinery. Now, new research shows how an enzyme called KDM4B "reads" one and "erases" another so-called epigenetic mark on a single histone protein during the generation of sex cells in mice. The researchers say the finding may one day shed light on some cases of infertility and cancer.

A summary of the work, a collaborative study among researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Rice University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was published online in the journal Nature Communications on Nov. 14.

"Our research gives us insight into how cells use this epigenetic machinery to shut off and protect parts of the genome during reproduction," says Sean Taverna, Ph.D., associate professor of pharmacology and molecular sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "Because KDM4B and its histone target are prevalent in mouse testes, and the absence of that histone target inhibits reproduction in a single-celled organism, we think this interaction could play a role in human infertility or other diseases."

At the heart of their new discovery, says Taverna, is the fact that genes housed in a cell's nucleus are not the whole story when it comes to the proteins they ultimately make. If genes are the sentences of a book, the story can be altered dramatically depending on which sentences are read and skipped over, and in what order. Histone proteins, Taverna explains, act like removable tape sealing closed particular pages of the book. When DNA is wrapped around them, genetic regions are "silenced" and go unread by other proteins -- a classic epigenetic control mechanism, since it changes how the genome is read without changing its sentences.

Histones are frequently controlled through small chemical "tags," especially methyl groups, which can be attached to and detached from specific spots on histone proteins. To advance its understanding of this process, Taverna's lab had previously turned to a one-celled organism, Tetrahymena thermophila, with an unusual trait: It has not one but two nuclei. The DNA in one nucleus is active and used for making proteins, while the DNA in the other is "silent" except during mating. That research revealed a new site for methyl groups on one histone. That spot, a lysine known as H3K23, has little to no methyl tags in active Tetrahymena nuclei but is loaded up with three methyl groups (H3K23me3) in "mating nuclei" undergoing early meiosis, the special version of cell division that creates sex cells.

In those experiments on Tetrahymena, the team learned that H3K23me3 appears in regions of the genome that should never be cut by enzymes during meiosis. DNA cuts normally occur during meiosis to allow for the mixing of genetic material and the proper sorting out of chromosomes in dividing cells, so H3K23me3 could protect nearby regions of the genome by "taping them up" so they can't be accessed.

In a hunt for what controls that part of the process, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison led by John Denu, Ph.D., developed a way to find out which proteins bind to which histone tags. Specifically, they identified a family of three similar enzymes called lysine demethylases, or KDM4s, which have been implicated in the development of some cancers in humans. KDM4A binds H3K23me3 plus two other histone tags and KDM4C binds another histone tag, but KDM4B binds only H3K23me3.

The researchers wondered what feature enables the three KDM4s to be so selective in their binding, so colleagues at Rice University, led by George Phillips, Ph.D., picked up the research baton at that point to understand their selectivity by solving their 3-D structures.

While KDM4B's structure proved elusive, the scientists were able to figure out the structure of KDM4A bound to H3K23me3. By comparing the differences between the KDM4s and by tweaking three of KDM4A's amino acid building blocks to make it act like KDM4B, the scientists report they were able to learn the basis for the binding preferences of all three KDM4s.

"Now that we know the 'rules' that determine how KDM4s bind, we can imagine ways to intervene to change their interactions with histone tags," says Taverna. "That in turn means we can test what happens when we enhance their activity or turn it down, and better understand their roles in disease."

To that end, biochemical tests revealed that after KDM4B "reads" H3K23me3, it "erases" the methyl groups from a nearby lysine, H3K36me3. The researchers say that more work is needed to understand the significance of this rare combination of activities, but Taverna speculates that the "demethylation" -- that is, removing the epigenetic marks -- of H3K36 helps to "tape up," silence and protect nearby DNA.

"We know from our work in Tetrahymena that H3K23me3 is most often found in regions of the genome that should never suffer DNA damage because that would harm reproduction," he says. "During meiosis, when H3K23me3 is most prevalent, DNA is prone to damage, which explains why Tetrahymena lacking H3K23me3 struggle to reproduce."

To see if H3K23me3 plays a role in mammalian reproduction, Taverna's group, led by postdoctoral fellow Kimberly Stephens, Ph.D., looked for its prevalence in rodents and found it and KDM4B to be increased in immature sperm undergoing early meiosis. (Since early meiosis occurs in females as they develop in the womb, the team was unable to examine immature eggs.)

"While our experiments offer no proof that defects in the KDM4B-H3K23me3 interaction cause infertility in mammals, all of the signs point in that direction," says Taverna, "and we definitely plan to study it further."

Other authors of the report include Romeo Papazyan, Ana Raman and Jeremy Thorpe of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Zhangli Su, Jin-Hee Lee, Kimberly Krautkramer, Melissa Boersma and Vyacheslav Kuznetsov of the University of Wisconsin-Madison; Fengbin Wang and Mitchell Miller of Rice University; and Ekaterina Voronina of the University of Montana.