News

Newswise —

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) develop with time and in stages. Following the initiation of drinking, some people progress to problem drinking, and then develop a “cluster” of specific problems to comprise an AUD. However, not all stages of AUD development have been studied equally. This report examines high-risk families to understand underlying influences across multiple stages of AUD development.

Researchers scrutinized four transitions in AUD development using data on adolescents and young adults from high-risk families: time to first drink, first drink to first problem, first drink to first diagnosis, and first problem to first diagnosis. Potential influences included parental AUD, parental separation, peer substance use, ever use of marijuana by offspring, trauma exposures, and different psychopathologies across transitions.

Results showed that significant influences across all transitions were fairly consistent, with externalizing psychopathologies and ever use of marijuana increasing the likelihood of transition at each stage. Peer and parental influences – especially maternal AUD – were linked to initiation and some later stages. Given increasingly permissive attitudes toward marijuana use in the United States, the authors suggest that more research be directed toward understanding the association of AUD development with marijuana use.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise —

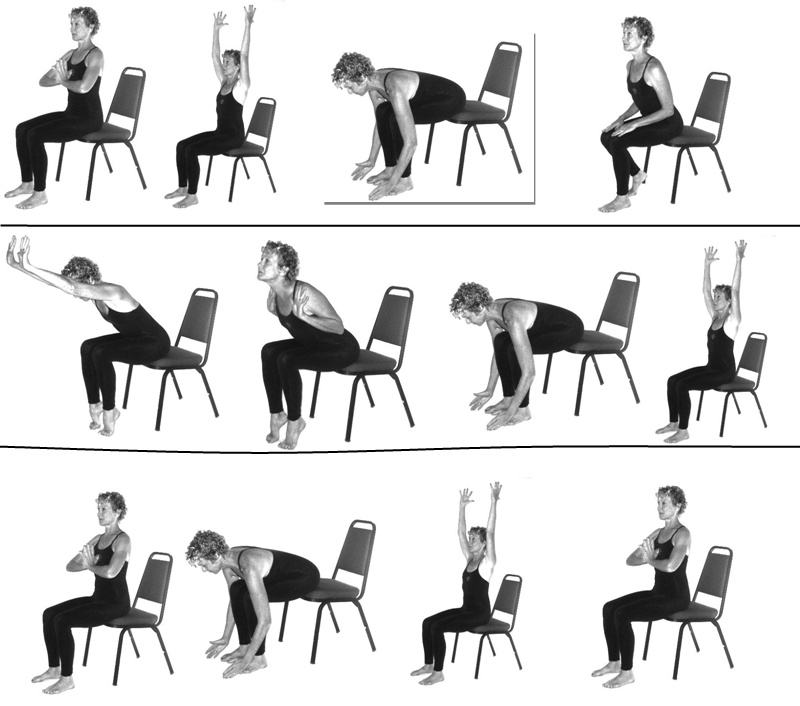

For the millions of older adults who suffer from osteoarthritis in their lower extremities (hip, knee, ankle or foot), chair yoga is proving to be an effective way to reduce pain and improve quality of life while avoiding pharmacologic treatment or adverse events. A new study, conducted by researchers at Florida Atlantic University and published in the current issue of the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, is the first randomized controlled trial to examine the effects of chair yoga on pain and physical function in older adults with osteoarthritis. For the study, researchers randomly assigned 131 older adults with osteoarthritis to either the “Sit ‘N’ Fit Chair Yoga©” program developed by Kristine Lee or a health education program. Participants attended 45-minute sessions twice a week for 8 weeks. Researchers measured pain, pain interference (how it affects one’s life), balance, gait speed, fatigue and functional ability, before, during and after the sessions.

Results from the study found that participants in the chair yoga group, compared to those in the health education program, showed a greater reduction in pain and pain interference during their sessions, and that reduction in pain interference lasted for about three months after the 8-week chair yoga program was completed. The 8-week chair yoga program also was associated with reductions in fatigue and improvement in gait speed during the study session, but not post session.

“With osteoarthritis-associated pain, there is interference in everyday living, limiting functional and social activities as well as diminishing life enjoyment,” said Juyoung Park, Ph.D., co-author and co-principal investigator of the study, Hartford Geriatric Social Work Faculty Scholar and an associate professor in FAU’s College for Design and Social Inquiry. “The effect of pain on everyday living is most directly captured by pain interference, and our findings demonstrate that chair yoga reduced pain interference in everyday activities.”

Regular exercise has proven to help relieve osteoarthritis pain, however, the ability to participate in exercise declines with age, and many dropout before they can even receive benefits. Although the Arthritis Foundation recommends yoga to reduce joint pain, improve flexibility and balance, and reduce stress and tension, many older adults cannot participate in standing exercises because of lack of muscle strength, pain and balance as well as the fear of falling due to impaired balance. Chair yoga is practiced sitting in a chair or standing while holding the chair for support, and is well suited to older adults who cannot participate in standing yoga or exercise.

“Currently, the only treatment for osteoarthritis, which has no cure, includes lifestyle changes and pharmacologic treatments that are not without adverse events,” said Ruth McCaffrey, D.N.P., A.R.N.P., co-author and emeritus professor in FAU’s College of Nursing. “The long-term goal of this research is to address the non-pharmacologic management of lower extremity osteoarthritis pain and physical function in older adults, and our study provides evidence that chair yoga may be an effective approach for achieving this goal.”

The overall goal of this interdisciplinary program is to decrease pain, and improve physical and psychosocial functions of elderly individuals with osteoarthritis who are unable to participate in other exercise and yoga programs.

Park and McCaffrey conducted the study with Patricia Liehr, Ph.D., R.N., co-principal investigator, co-author and a professor in FAU’s College of Nursing; David Newman, Ph.D., co-author and an assistant professor in FAU’s College of Nursing; and Joseph G. Ouslander, M.D., co-author, senior associate dean of geriatric programs and chair and professor of the Department of Integrated Medical Science in FAU’s Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine.

“The potential impact of this study on public health is high, as this program provides an approach for keeping community-dwelling elders active even when they cannot participate in traditional exercise that challenges their balance,” said Liehr.

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis in older adults. Consequences associated with osteoarthritis include pain, joint stiffness and functional limitation of activities of daily living. Osteoarthritis is the leading cause of long-term disability among older adults and affects more than 33 percent of people over the age of 65 in the U.S. Annually, osteoarthritis accounts for more than 11 million physician and outpatient visits, 662,000 hospitalizations and an estimated $81 billion in costs for medical and surgical treatments. The World Health Organization estimates that osteoarthritis affects about 10 percent of men and 18 percent of women worldwide.

This project is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) through grant number 1R15AT007352-01A1.

Newswise —

Individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes have lower physical activity (PA) levels than the general population. Given the known health benefits of PA, it is important that lifestyle treatment programs for this population produce significant long-term improvements in PA. This study used a waist-worn tracking device to assess PA levels among 2400 older adults with type 2 diabetes over four years. Participants who were randomly assigned to the lifestyle treatment group were over two times as likely to achieve the study PA goal of at least 175 minutes/week. In addition, they were 1.5 times more likely to maintain this level of PA after four years, compared to those assigned to a basic diabetes education group. Yet, not all participants met the PA goal and some performed very little PA after four years. So, lifestyle programs may need to better address barriers to maintaining PA so that this behavior becomes a life-long habit.

For more information about this research, view the abstract or contact the investigators.

Newswise — CHICAGO -

Northwestern Medicine scientists have discovered the genetic driver of a rare and lethal childhood leukemia and identified a targeted molecular therapy that halts the proliferation of leukemic cells. The finding also has implications for treating other types of cancer.

Mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) primarily strikes newborns and infants. Less than 10 to 20 percent of those children (300 cases are seen in the United States per year) live no more than five years after being diagnosed.

“We’ve spent the last 20 years in my laboratory trying to molecularly understand how MLL translocations cause this rare and devastating form of leukemia in children so that we can use this information to develop an effective therapy for this cancer,” said lead investigator Ali Shilatifard. “Now we’ve made a fundamentally important breakthrough.”

The paper was published Jan. 5 in the journal Cell.

Shilatifard, the chair and professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics and professor of pediatrics, his graduate student Kevin Liang and their colleagues at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine are extremely hopeful about this breakthrough and are in the process of pushing their findings into clinic for the treatment of childhood leukemia.

Shilatifard also is a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

“Mixed lineage leukemia is caused when an errant chromosome 11 on the MLL gene breaks and attaches to other chromosomes such as chromosome 19, where it doesn’t belong,” said Liang, the paper’s first author. “The mutation produces a protein that drives the pathogenesis of leukemia.”

Most research related to this cancer has focused on the errant version of chromosome 11. But there are two copies of chromosome 11, and the Shilatifard group wanted to investigate the wild-type version. Shilatifard’s laboratory discovered that individual cells with the pediatric leukemia had extremely low levels of a protein produced by the wild-type MLL gene. Shilatifard and Liang reasoned if they could beef up the levels of the wild-type MLL protein, it would displace the mutated version that drives cancer, and it could cure leukemia.

Through their detailed molecular and biochemical screens, Shilatifard’s lab identified a compound that stabilized the wild-type MLL and interfered with the mutant protein driving leukemia. To test its effectiveness, in collaboration with John Crispino’s lab of Northwestern University and his fellow Andrew Volk, they grew mixed lineage leukemia cells in a culture and transplanted them into mice. They then injected the therapeutic compound into the mice. The result: the wild-type MLL bounced back to healthy levels, and the leukemic cells were not able to grow as rapidly.

Northwestern scientists are now synthesizing better compounds and hope to eventually launch a Phase I trial to test these compounds in Chicago.

Other Northwestern authors in the manuscript include Stacy A. Marshall, Ashley R. Woodfin, Elizabeth T. Bartom and Edwin R. Smith. The study was also done in collaboration with colleagues at Stowers Institute, where Shilatifard’s laboratory used to be prior to his joining Northwestern Medicine in 2014.

Shilatifard’s laboratory is supported by the Outstanding Investigator Award from the National Cancer Institute grant R35CA197569 of the National Institutes of Health.

Newswise — Montreal, –

New research findings show that bilingual people are great at saving brain power, that is. To do a task, the brain recruits different networks, or the highways on which different types of information flow, depending on the task to be done. The team of Ana Inés Ansaldo, PhD, a researcher at the Centre de recherche de l’Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal and a professor at Université de Montréal, compared what are known as functional brain connections between seniors who are monolingual and seniors who are bilingual. Her team established that years of bilingualism change how the brain carries out tasks that require concentrating on one piece of information without becoming distracted by other information. This makes the brain more efficient and economical with its resources.

To arrive at this finding, Dr. Ansaldo’s team asked two groups of seniors (one of monolinguals and one of bilinguals) to perform a task that involved focusing on visual information while ignoring spatial information. The researchers compared the networks between different brain areas as people did the task. They found that monolinguals recruited a larger circuit with multiple connections, whereas bilinguals recruited a smaller circuit that was more appropriate for the required information. These findings were published in the Journal of Neurolinguistics.

Two different ways of doing the same taskThe participants did a task that required them to focus on visual information (the colour of an object) while ignoring spatial information (the position of the object). The research team observed that the monolingual brain allocates a number of regions linked to visual and motor function and interference control, which are located in the frontal lobes. This means that the monolingual brain needs to recruit multiple brain regions to do the task.

“After years of daily practice managing interference between two languages, bilinguals become experts at selecting relevant information and ignoring information that can distract from a task. In this case, bilinguals showed higher connectivity between visual processing areas located at the back of the brain. This area is specialized in detecting the visual characteristics of objects and therefore is specialized in the task used in this study. These data indicate that the bilingual brain is more efficient and economical, as it recruits fewer regions and only specialized regions,” explained Dr. Ansaldo.

Bilinguals have a double advantage as they ageBilinguals therefore have two cognitive benefits. First, having more centralized and specialized functional connections saves resources compared to the multiple and more diverse brain areas allocated by monolinguals to accomplish the same task. Second, bilinguals achieve the same result by not using the brain’s frontal regions, which are vulnerable to aging. This may explain why the brains of bilinguals are better equipped at staving off the signs of cognitive aging or dementia.

“We have observed that bilingualism has a concrete impact on brain function and that this may have a positive impact on cognitive aging. We now need to study how this function translates to daily life, for example, when concentrating on one source of information instead of another, which is something we have to do every day. And we have yet to discover all the benefits of bilingualism,” concluded Dr. Ansaldo.

ReferenceBerroir P., Ghazi-Saidi L., Dash T., Adrover-Roig D., Benali H., Ansaldo AI. “Interference control at the response level: Functional networks reveal higher efficiency in the bilingual brain”, Journal of Neurolinguistics (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2016.09.007. Status: In Press.

About the author Ana Inés Ansaldo, PhD, is a researcher at the Research Centre of the Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal (IUGM) and a professor at the School of Speech Therapy and Audiology at Université de Montréal.

About the Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal (IUGM)The IUGM has 446 short-term and long-term beds and an ambulatory centre. It has what is considered to be the largest francophone research centre in the field of aging. A member of Université de Montréal's larger excellence in health network, the IUGM opens its doors every year to hundreds of students, trainees and researchers. Since April 1, 2015, the IUGM has been part of the CIUSSS du Centre-Sud-de-l’Île-de-Montréal.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise —

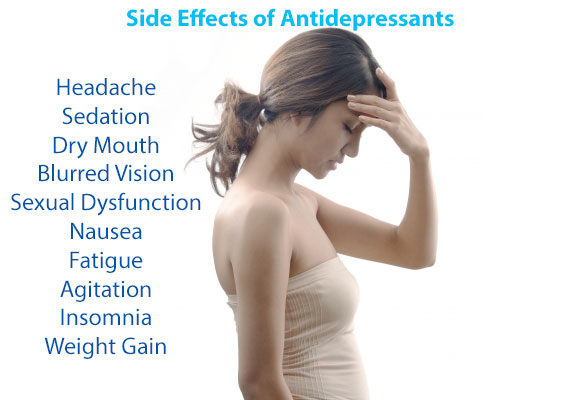

Patients who take medication for depression report more side effects if they also suffer from panic disorder, according to a new study led by researchers from the University of Illinois at Chicago published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The researchers looked at data from 808 patients with chronic depression who were given antidepressants as part of the Research Evaluating the Value of Augmenting Medication with Psychotherapy (REVAMP) trial. Of those patients, 85 also had diagnoses of panic disorder.

Among all participants, 88 percent reported at least one side effect during the 12 week trial, which ran from 2002 through 2006. Every two weeks, antidepressant side effects were assessed, and categorized as gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, dermatological, neurological, genitourinary, sleep, or sexual functioning.

The researchers found that patients with depression and panic disorder were more likely than those with only depression to self-report gastrointestinal (47 percent vs. 32 percent), cardiovascular (26 percent vs. 14 percent), neurological (59 percent vs. 33 percent), and genital/urinary side effects (24 percent vs. 8 percent). Co-occurring panic disorder was not associated with eye or ear issues or dermatological, sleep or sexual functioning side effects compared to participants without panic disorder.

“People with panic disorder are especially sensitive to changes in their bodies,” said Stewart Shankman, professor of psychology and psychiatry at UIC and corresponding author on the paper. “It’s called ‘interoceptive awareness.’“Because these patients experience panic attacks — which are sudden, out-of-nowhere symptoms that include heart racing, shortness of breath, and feeling like you’re going to die — they are acutely attuned to changes in their bodies that may signal another panic attack coming on. So it does make sense that these tuned-in patients report more physiological side effects with antidepressant treatment.”

Response to antidepressants varies greatly, and side effects are common. Many patients who experience side effects switch medication or change dosage. Some discontinue therapy altogether.

Participants with co-occurring panic disorder were also more likely to report a worsening of their depressive symptoms over the 12 weeks if they reported multiple side effects.

“In patients with panic disorder, the more side effects they reported, the more depressed they got,” said Shankman. “Whether the side effects are real or not doesn’t matter, but what was real was that their depression worsened as a function of their side effects.”

Shankman cautions that physicians and therapists should be aware that their patients with panic disorder may report more side effects, and they should “do a thorough assessment of these side effects to try to tease out what might be the result of hypersensitivity, or what might be a side effect worth switching doses or medications for.”

Co-authors on the paper are Stephanie Gorka, and Andrea Katz of UIC; Daniel Klein of Stony Brook University; Dr. John Markowitz of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; Bruce Arnow, Rachel Manber and Alan Schatzberg of the Stanford University School of Medicine; Barbara Rothbaum of Emory University School of Medicine; Dr. Michael Thase of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Dr. Martin Keller of Brown University School of Medicine; Dr. Madhukar Trivedi of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; and Dr. James Kocsis of Weill-Cornell Medical College.

This research was supported by grants U01 MH62475, U01 MH61587, U01 MH62546, U01 MH61562, U01 MH63481, U01 MH62465, U01 MH61590, U01 MH61504 and U01 MH62491 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Newswise —

Overweight and obese children are at the highest risk for the most common complications from surgery, an infection at the site of the surgical procedure. This according to a new study, recently published in the medical journal, Surgical Infections.While obesity is a well-known risk factor for surgical site infections (SSI) among adult patients, this is the first research showing it is equally significant in pediatric populations. And since the incidence of childhood obesity in the US has nearly tripled since the 1970s, this indicates more and more children will possibly be at risk for these infections.

“Research on this topic among children and adolescents is scarce,” said Catherine Hunter, MD, Pediatric Surgeon at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and an Assistant Professor of Surgery and Pediatrics, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. (https://www.luriechildrens.org/en-us/care-services/find-a-doctor/Pages/Hunter_Catherine_3205.aspx) “The information from this first-of-its-kind study can now be used in assessing and counseling preoperative pediatric surgical patients and their families.”

The study, titled “Overweight and Obese Pediatric Patients Have an Increased Risk of Developing a Surgical Site Infection,” included a search of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) National Surgical Quality Improvement Program-Pediatric (NSQIP-P) database, as well as a follow-up single center retrospective review. The latter review allowed for a more detailed analysis using specific outcomes variables that could not be analyzed using the NSQIP-P database, including looking at those overweight and obese pediatric patients who developed SSI despite having few other identifiable risk factors for infection.

Cases from a total of 1,380 patients aged 2-18 (mean patient age 10.4 years) from the NSQIP-P database who had undergone major surgical procedures in 2012 and 2013 and who developed post-operative wound infections up to 30 days after surgery were reviewed. Patients were classified as underweight, normal/healthy weight, overweight, or obese, according to standard CDC pediatric growth charts, with a 95% confidence interval.

Forty-percent of these patients who had SSIs were overweight or obese and without differences in gender.

In the single site retrospective review, data from another 115 patients were considered. Of this population the average age was slightly younger at 9 years and 30% were overweight or obese.

“When considering children, adolescents and adults, there are several theories as to why overweight or obese patients are at higher risk for infection,” said Dr. Hunter. “These include impaired wound healing due to the lower oxygen tension found in the excess fat tissue surrounding the wound as well as impaired lymphocyte responsiveness. However more studies need to look at this further.”

Lurie Children’s is the only children’s hospital in Illinois and one of only a very few in the country, recognized by the American College of Surgeons as a Level I pediatric surgery center, the highest quality designation possible. It is ranked as one of the nation’s top children’s hospitals in the U.S. News & World Report, and is the pediatric training ground for Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Last year, the hospital served more than 174,000 children from 50 states and 48 countries.#######

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise — EAST LANSING, Mich. –

Michigan State University researchers have discovered that a chemical compound, and potential new drug, reduces the spread of melanoma cells by up to 90 percent.

The man-made, small-molecule drug compound goes after a gene’s ability to produce RNA molecules and certain proteins in melanoma tumors. This gene activity, or transcription process, causes the disease to spread but the compound can shut it down. Up until now, few other compounds of this kind have been able to accomplish this.

“It’s been a challenge developing small-molecule drugs that can block this gene activity that works as a signaling mechanism known to be important in melanoma progression,” said Richard Neubig, a pharmacology professor and co-author of the study. “Our chemical compound is actually the same one that we’ve been working on to potentially treat the disease scleroderma, which now we’ve found works effectively on this type of cancer.”

Scleroderma is a rare and often fatal autoimmune disease that causes the hardening of skin tissue, as well as organs such as the lungs, heart and kidneys. The same mechanisms that produce fibrosis, or skin thickening, in scleroderma also contribute to the spread of cancer.

Small-molecule drugs make up over 90 percent of the drugs on the market today and Neubig’s co-author Kate Appleton, a postdoctoral student, said the findings are an early discovery that could be highly effective in battling the deadly skin cancer. It’s estimated about 10,000 people die each year from the disease.

Their findings are published in the January issue of Molecular Cancer Therapeutics.

“Melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer with around 76,000 new cases a year in the United States,” Appleton said. “One reason the disease is so fatal is that it can spread throughout the body very quickly and attack distant organs such as the brain and lungs.”

Through their research, Neubig and Appleton, along with their collaborators, found that the compounds were able to stop proteins, known as Myocardin-related transcription factors, or MRTFs, from initiating the gene transcription process in melanoma cells. These triggering proteins are initially turned on by another protein called RhoC, or Ras homology C, which is found in a signaling pathway that can cause the disease to aggressively spread in the body.

The compound reduced the migration of melanoma cells by 85 to 90 percent. The team also discovered that the potential drug greatly reduced tumors specifically in the lungs of mice that had been injected with human melanoma cells.

“We used intact melanoma cells to screen for our chemical inhibitors,” Neubig said. “This allowed us to find compounds that could block anywhere along this RhoC pathway.”

Being able to block along this entire path allowed the researchers to find the MRTF signaling protein as a new target.

Appleton said figuring out which patients have this pathway turned on is an important next step in the development of their compound because it would help them determine which patients would benefit the most.

“The effect of our compounds on turning off this melanoma cell growth and progression is much stronger when the pathway is activated,” she said. “We could look for the activation of the MRTF proteins as a biomarker to determine risk, especially for those in early-stage melanoma.”

According to Neubig, if the disease is caught early, chance of death is only 2 percent. If caught late, that figure rises to 84 percent.

“The majority of people die from melanoma because of the disease spreading,” he said. “Our compounds can block cancer migration and potentially increase patient survival.”

The National Institutes of Health and MSU's annual Gran Fondo cycling event, which raises money for skin cancer research, funded the study. Additional researchers from MSU and the University of Michigan contributed to the project.

###

Newswise —

Chicagoland families affected by autism can participate in the nation’s largest study to uncover genetic links to the condition by attending an on-site registration and data collection event in the western suburbs, Saturday, January 14. Families with a loved one on the autism spectrum are asked to share demographic, medical and behavioral information at: Right Fit Sports-Fitness-Wellness, 7101 S Adams, Willowbrook, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.; or Turning Pointe, 1500 West Ogden Avenue, Naperville, 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. Participants with autism will receive a $50 gift card in the mail upon completion of their study.

The research project, called SPARK (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge), is hoping to collect family information and DNA samples from 50,000 people with autism and their family members. In Chicago, SPARK has partnered exclusively with Rush University Medical Center (RUMC).Families will be asked to fill out a short on-line family history form and complete a DNA test consisting of a simple spit sample or cheek swab. Participants are encouraged to register for the event in advance, however walk-ins are welcome. Those who register in advance will receive one free personal fitness session from Right Fit Sports Fitness Wellness. Right Fit specializes in movement and fitness programs for youth and adults on the autism spectrum.

To register or for more information, contact the Autism Assessment, Research, Treatment and Services Center (AARTS) at Rush, (312) 563-2765, or email: Kathryn_A_Heerwagen@rush.edu.

Autism is known to have a strong genetic component. To date, approximately 50 genes have been identified that almost certainly play a role in autism, and scientists estimate that an additional 300 or more are involved.

For those who want to participate, but can’t attend the on-site testingor for more information, visit:www.SPARKforAutism.org/rush. The AARTS Center provides unparalleled expertise in diagnosis, treatment and research for individuals with autism spectrum disorder.

Newswise —

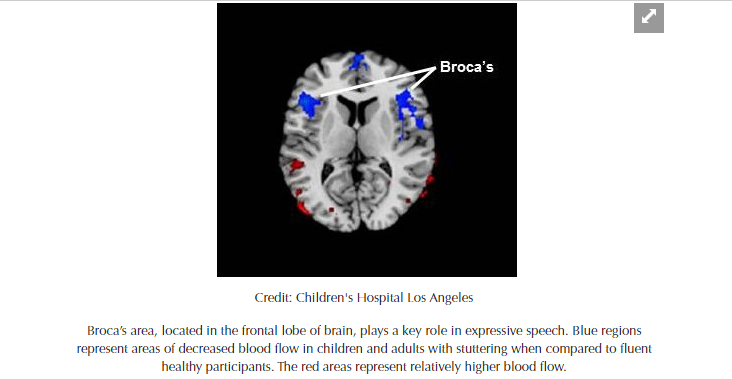

A study led by researchers at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles demonstrates what lead investigator Bradley Peterson, MD, calls “a critical mass of evidence” of a common underlying lifelong vulnerability in both children and adults who stutter. They discovered that regional cerebral blood flow is reduced in the Broca’s area – the region in the frontal lobe of the brain linked to speech production – in persons who stutter. More severe stuttering is associated with even greater reductions in blood flow to this region.

In addition, a greater abnormality of cerebral blood flow in the posterior language loop, associated with processing words that we hear, correlates with more severe stuttering. This finding suggests that a common pathophysiology throughout the neural “language” loop that connects the frontal and posterior temporal lobe likely contributes to stuttering severity.

Peterson, who is director of the Institute for the Developing Mind at CHLA and a professor of the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, says that such a study of resting blood flow, or perfusion, has never before been conducted in persons who stutter. His team also recently published a study using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy to look at brain regions in both adults and children who stutter. Those findings demonstrated links between stuttering and changes in the brain circuits that control speech production, as well as those supporting attention and emotion. The present blood flow study adds significantly to the findings from that prior study and furthermore suggests that disturbances in the speech processing areas of the brain are likely of central importance as a cause of stuttering.

According to Peterson, the new study – published on December 30 in the journal Human Brain Mapping – provides scientists with a completely different window into the brain. The researchers were able to zero in on the Broca’s area as well as related brain circuitry specifically linked to speech, using regional cerebral blood flow as a measure of brain activity, since blood flow is typically coupled with neural activity.

“When other portions of the brain circuit related to speech were also affected according to our blood flow measurements, we saw more severe stuttering in both children and adults,” said first author Jay Desai, MD, a clinical neurologist at CHLA. “Blood flow was inversely correlated to the degree of stuttering – the more severe the stuttering, the less blood flow to this part of the brain,” said Desai, adding that the study results were “quite striking.”

Additional contributors to the study include Ravi Bansal, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the Keck School of Medicine of USC; Yuankai Huo and Zhishun Wang, Columbia University; Steven C. R. Williams, David Lythgoe and Fernando O. Zelaya, King’s College, London, UK. This work was supported in part by Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, the National Institute of Mental Health grant K0274677, the Milhiser family fund and the Murphy endowment at Columbia University.

About Children’s Hospital Los AngelesChildren's Hospital Los Angeles has been named the best children’s hospital in California and among the top 10 in the nation for clinical excellence with its selection to the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll. Children’s Hospital is home to The Saban Research Institute, one of the largest and most productive pediatric research facilities in the United States. Children’s Hospital is also one of America's premier teaching hospitals through its affiliation since 1932 with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. For more information, visit CHLA.org. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and LinkedIn, or visit our blog at http://researchlablog.org/.