News

Credit Newswise —

Latinas who eat processed meats such as bacon and sausage may have an increased risk for breast cancer, according to a new study that did not find the same association among white women.

The study, published Feb. 22 in the journal Cancer Causes Control, suggests that race, ethnicity, genetics, culture and lifestyle choices could all affect cancer risk, said Mariana Stern, senior author and director of graduate programs in molecular epidemiology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

"Few studies look at breast cancer risk factors specific to Latinas," said Stern, an associate professor in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at Keck Medicine of USC. "Our focus was to understand if meat consumption is associated with breast cancer and whether there are differences between Latinas and white women. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has looked at meat intake among Latinas."

The findings came months after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared processed meat a carcinogen that increases the risk of colorectal cancer. Stern was among the panel of international scientists who helped come to that conclusion.

"The group was on the fence about concluding that processed meat intake may cause breast cancer and ultimately decided not to make that edict based on insufficient data from studies," Stern said. "Now a new study shows there is an association between processed meat and breast cancer for one understudied population. In light of the WHO report, this discovery could be a wake-up call about the negative health effects associated with consuming processed meat such as bacon, beef jerky and lunch meats."

Red meats and tuna

In the study, Latinas who consumed about 20 grams of processed meat per day (the equivalent of a strip of bacon) were 42 percent more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer compared to Latinas who ate little or no processed meats, said Andre Kim, lead author and a USC molecular epidemiology doctoral student.

"We're not entirely sure why processed meat association was restricted to Hispanics, especially since we know processed meats are carcinogens," Kim said.

Researchers also looked at consumption of red meats, poultry, all fish and just tuna. White women who ate an average of 14 grams of tuna daily (roughly the size of a thimble) were 25 percent more likely to have breast cancer than those who did not. The association for tuna on Latinas was comparable but not statistically significant.

While many fish contain omega-3 and other fatty acids, many also contain contaminant metals such as mercury and cadmium. Tuna has been reported to have a higher proportion of these contaminants, which may activate estrogen receptors and increase breast cancer risk, Stern said.

As a caveat, the authors noted the association between increased breast cancer risk and tuna could have been driven by chance because the two data sets researchers used had different ways of collecting tuna intake information.

The study included 7,470 participants derived from two other studies that included women who lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. Their ages ranged from 25 to 79. The control groups were random women in the same neighborhoods who did not have breast cancer.

In one of these studies, bilingual interviewers recorded dietary intake data using a questionnaire that captured more than 300 food items. In the other one, bilingual interviewers recorded dietary intake using a questionnaire that captured 85 food items. USC researchers harmonized information for meat intake from the two studies to make a comparable data set.

Confirming findings

Moving forward, Stern and Kim are interested in confirming their findings by looking at other large data sets involving Latinas with breast cancer.

"One hypothesis for our different findings for processed meats between Latinas and non-Latinas is that the timing of exposure is important," Kim said. "More attention is being given to exposures during adolescence because that is a key period in breast tissue development. Hispanics might experience worse dietary intake compared to white women in this time period."

###

Researchers from the University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Institute of Human Genetics at the University of California, San Francisco, Cancer Prevention Institute of California and Stanford University School of Medicine, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública in Mexico, University of Louisville, John Hopkins University, University of Colorado, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital contributed to the study.

The research was funded by the California Department of Public Health, National Institutes of Health, California Breast Cancer Research Program, American Cancer Society and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Credit Newswise —

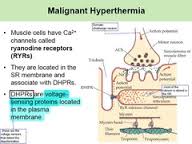

Debra Merritt, a Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA), has been on the board of directors for the Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States for the past 20 years. She is a staff CRNA who works primarily at Women’s Hospital Cone Day Surgery Center, but also administers anesthesia to patients at Moses Cone Health System and Wesley Long Surgery Center in North Carolina

Merritt is a highly sought-after lecturer on malignant hyperthermia at state and national meetings in the healthcare profession.

A published researcher, Merritt co-authored “Developing Effective Drills in Preparation for a Malignant Hyperthermia Crisis” in the March 2013 AORN Journal. In addition, she was one of three authors responsible for a chapter, “Malignant Hyperthermia: Dantrolene,” published in the 2010 book edition of Pharmacology for Nurse Anesthesiology.

Merritt has been practicing anesthesia since 1992 after graduating with a Master of Science in Nurse Anesthesia and a Bachelor of Science from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

A member of the AANA since 1990, she is an active member of several other associations, including the North Carolina Association of Nurse Anesthetists and Sigma Theta Tau, the National Honor Society of Nursing. Merritt has been an adjunct nursing instructor and an associate director of didactic education and research. Merritt resides in Elon, North Carolina.

These daily fluctuations might be subtle, but that doesn't mean they're not happening. By denying or resisting your own transitory nature, you will make yourself utterly miserable.

Most of us do pick up on these changes, whether we're tuned into them every second or every few days. (How many times have you been guilty of muttering, "I feel so fat today" to your best friend?)

Acknowledging them is not only okay, it's normal. Society likes to make women out as "crazy" for having feelings, intuition, and sensitivity. We're judged by standards that were never meant for us, thanks to the patriarchy and our sexually repressed Anglo-Saxon foundation.

Guess what? "Sensitivity" just means we have the gift of being able to pick up on subtle sh*t. If someone calls you "too sensitive," what they really mean "you're making me feel crazy because I can't see the subtle things you see, and I don't like that."

Immediately let go of any narrative you've been clinging to that your emotions or ability to perceive things make you crazy. They don't.

A problem arises, however, when you become deeply attached to only one part of your body's total experience. When your body isn't in the one exact state you are attached to, you might feel shame, anger, or sadness. Maybe you feel like you should look and feel a certain way all the time.

If you desperately crave arrival at an end point, where you can finally rest from the exhausting pursuit of your body's perfection, then it's time to let that go. There is no such end point. The only way you can rest is by letting go of the attachment.

How to do that? By realizing that these fluctuations are a very normal—healthy even—part of existing in a human body. Let's take a look at a handful of changes your body might go through on a daily basis that could trigger attachment anxiety.

On a Thursday you look in the mirror. You've been eating well since Sunday, crushing your workouts, and getting lots of sleep all week. You look at your naked body and think, God, yes! I look awesome. Then you put on something hot and go out to happy hour for margaritas and Mexican food.

You wake up on Friday morning to find a bloated hippopotamus looking back at you in the mirror. If you weighed yourself, you might even be up three to five pounds from the night before.

Now, let's look at the facts here. Did you gain a bunch of fat since yesterday? No, that's impossible. Is it all in your head? No, because as we've established already, you're not a crazy person. (You have a female superpower. You pick up on subtle changes.)

So what caused this overnight change? Water retention. Due to some awesome chemistry between salt, water, carbs, and even alcohol, your body can either be holding a little water or a lot.

Bodybuilders and fitness models manipulate the way their bodies hold water in order to "peak," which just means they get as dehydrated and "dry" as possible for a very temporary appearance of maximum leanness.

The "water pills" and diuretics that are sold over the counter create a similar effect. The results of a dedicated peaking protocol, which have nothing to do with fat, are dramatic. You can go from pretty lean to "holy sh*t, I'm shredded" just by playing with water retention. However, it's extremely temporary, and in many cases, it's also wildly unhealthy.

At some point in your life, you may have accidentally "peaked." In my example above, you might have felt de-puffed on Thursday night thanks to a week of drinking lots of water, sweaty workouts, and eating low-sodium and low-carb home-cooked dinners. By attaching your happiness to this one small part of the experience, of having a body in which you retain very little water, you set yourself up to feel awful the next day when it shifted again.

It's also worth mentioning here that the stress hormone cortisol causes you to hold water in a major way. So if you've been restful, sleeping a lot, and happy all week, your cortisol will be low, and therefore, so will your water-retention levels. This is one of the main reasons for that mysterious "vacation abs" phenomenon, when (despite eating whatever you want and not working out) your body looks inexplicably lean and sexy on vacation. If you hold a lot of water normally due to stress, suddenly being restful and joyful will bring about some fluctuations. Elevation, like traveling by plane, can also cause changes in water retention.

So what to do?

Stop worshipping one half of this cycle and condemning the other. There are certainly some habitual lifestyle factors worth considering and improving here, such as getting more sleep, lowering stress, drinking more water, and eating less processed foods. But water fluctuations are normal. Even someone who is super healthy will notice them from time to time. So find love for the puff.

To read full story click here

Credit JESSI KNEELAND

Scientists don’t know all the causes of autism, but they do know that certain genes and environmental factors can play a role in the broad spectrum of developmental disabilities that fall under the term. Gaining additional knowledge isn’t easy, however, because most of the nitty gritty brain research is done in rodents — animals that don’t mimic complex brain disorders well. Now, researchers in China say that they’ve managed to produce monkeys that display autism-like behaviors for the first time, according to a study published in Nature today. Their research, however, raises questions about scientists’ ability to create a non-human primate model of autism that’s actually valid.

SCIENTISTS INTRODUCED A HUMAN GENE INTO THE MONKEYS' DNA

To produce the monkeys, the scientists introduced a human gene called MeCP2 in the genome of macaques. The gene caused the monkeys to display behavioral symptoms akin to those seen in children with MeCP2 duplication syndrome — a rare disorder that causes autism-like behaviors. These symptoms include repetitive movements, anxiety, and decreased social interaction. In addition, the monkeys were able to pass the gene and their associated symptoms down to their offspring, which means these monkeys may give researchers a chance to study the genetics of autism spectrum disorders in a much more robust way than they’ve been able to in the past. Scientists might even be able to come up with treatments to reduce symptoms of autism in humans, the authors of the study say.

But other researchers have doubts about the effectiveness of using these primates to model human brain disorders. Unlike children who have the MeCP2 duplication syndrome, the monkeys in the experiment weren’t severely developmentally delayed; combined with the high cost of producing these animals, there are big enough problems to put the entire model into question.

"In all honesty, I’m not so excited about this study," says Hilde Van Esch, a geneticist at the University of Leuven in Belgium who studies MeCP2 duplication syndrome. Many children who have the duplication syndrome meet the formal criteria for an autism diagnosis, but they also tend to have symptoms that aren’t typical of autism, like "severe developmental delays, seizures, some [can’t] walk without aid," she says. The fact that these monkeys don’t have these problems is "surprising." And because the syndrome is rare in humans, it’s unclear how these monkeys might help autism research as a whole. "MeCP2 duplication syndrome is surely not ‘the’ prototype of autism," she says. "So the clinical utility of this model is, in my opinion, very low."

Huda Zoghbi, director of the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital, also thinks that the monkeys’ symptoms put the validity of the animal model into question. The monkeys failed to develop the cardinal features of the MeCP2 duplication syndrome, and only the male monkeys had social interaction deficits — a fact that the authors of the study don’t explain. That means that the monkeys "don’t reproduce the human duplication disorder," she says. Because of these uncertainties, using the monkeys to model autism doesn’t make sense, she says.

THESE MONKEYS "ARE THE FIRST PRIMATE MODELS OF AUTISM."

The scientists who produced the monkeys are far more optimistic. These monkeys "are the first primate models of autism," says Zilong Qiu, a neuroscientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and a co-author of the study. "I’m thrilled by the possibility that we may be able to reverse the genetic causes in the transgenic autism monkey model."

In humans, MeCP2 duplication syndrome occurs when humans have extra copies of the MeCP2 genes. To replicate this syndrome in macaques, scientists genetically modified monkey embryos by introducing the MeCP2 gene into the monkey’s DNA. Then, they implanted over 50 embryos into 18 surrogate monkeys. A total of nine female surrogates became pregnant, but only eight baby monkeys were born alive. These macaques displayed some of the symptoms typical of children with MeCP2 duplication syndrome, including anxiety, repetitive behaviors, what Qiu refers to as "defects in social interactions" with other monkeys. In addition, the researchers used sperm from the first generation of monkeys to create a second generation of transgenic monkeys who also displayed autism-like behaviors.

Now that the monkeys have been developed, Qiu and his team of researchers have begun to use brain imaging technology to identify brain circuits that play a role in the monkeys’ autism-like behaviors. If the researchers can do that, they might be able to "rescue the affected brain circuits," Qiu says — and alter the monkeys’ autism-like behaviors.

As a model for autism, the monkeys "aren’t perfect," but they could be better than mice designed to replicate the syndrome, says Alysson Muotri, a human brain development researcher at the University of California–San Diego. "At least the [monkeys] could mimic autism-like behaviors," he says. Still, it’s unclear if the monkeys "can actually generate novel insights into the human condition," Muotri says. The study published today doesn’t reveal anything new — and that’s a bit of a letdown, he says. "I would expect to learn some new biology here, but I have not."

"I WOULD EXPECT TO LEARN SOME NEW BIOLOGY HERE, BUT I HAVE NOT."

Even if the researchers can improve their model, the high cost of producing the monkeys will pose an important barrier to further research. "Primate studies are extremely expensive — the animals live a long time and have long gestation periods compared to rodents," Zoghbi says. "I think we should always make sure that our effort produces results worth the investment." Van Esch agrees. "In my opinion, there are easier and cheaper ways to study neurodevelopmental disorders."

It’s also worth noting that DNA isn’t the only factor involved in autism spectrum disorders; environmental factors, like pesticides, have been linked to autism as well. So even though there’s a lot of value in studying how human genes lead to autism-like behaviors, DNA is just one piece of the puzzle.

The fact that monkeys are more closely related to humans shouldn’t be used to justify using an inadequate model, Zoghbi says. "Decades of research using mice that do not [mimic features of the syndrome as closely as possible] resulted in a lot of research that can’t be translated, so it is important that we hold same standards to non-human primate models." And that means stating the limitations of each new animal model clearly. "We have to be very careful when there is a lot of desperation from human patients for answers to their problem — whether that be autism or Alzheimer’s or cancer or any other dreaded disease."

Credit Arielle Duhaime-Ross

You see them everywhere, on people’s wrists and in annoyingly contagious adverts but could wearable fitness devices be put to even better use? Yes, they monitor your day to day ‘fitness’, such things as how many steps you’re taking and how much sleep you’re getting but if they are able to gather this sort of information could they not also gather data that tells you there is something seriously wrong?

That is certainly the hope and idea behind aparito, an app and wearable device that aims to help children suffering from a variety of diseases. Founder and director of aparito, Dr. Elin Haf Davies, who has worked as a children’s nurse for many years, explains how aparito was born out of a ‘frustration that we were relying on very sterile snapshots of data that tell you how the patient is doing on a hospital visit but which doesn’t actually tell you anything about how they’re coping in day to day life at home.’

I hope our approach will contribute quite significantly to changing the way patients are in control of their own data.

The idea behind aparito is simple: to take information gathered by the wearable device, combine it with the patient’s perspective on how they are handling their illness. The data can be accessed by the patient’s doctor in real-time at all times, cutting out the need for all manner of long and arduous tests to get the same results.

The key to this is that the app and wearable device are designed to benefit both the patient and the doctor. The patient is able to keep track of their symptoms and therefore better manage their illness as well as knowing when to take medication. Meanwhile, the doctor is able to monitor the everyday activity of the patient.

To read full story Click Here

Credit Alex Moss

Researchers at Vanderbilt University have developed a technique to mimic complex systems of capillaries using cotton candy machines. The new technique is used in creating three-dimensional templates of the capillary system and is said to be a huge improvement over other methods.

Sugar wouldn't work in creating the threads needed for the template—it was too soluable—so the researchers turned to a special polymer for the job. After spinning a system of polymer threads, the researchers pour a gelatin mixture that includes human cells over the polymer structure. Once the mixture cools, the polymer threads dissolve, leaving behind an elaborate network of tiny passages.

"Some people in the field think this approach is a little crazy,” researcher Leon Bellan told Vanderbilt's research news site, “but now we’ve shown we can use this simple technique to make microfluidic networks that mimic the three-dimensional capillary system in the human body in a cell-friendly fashion."

Bellan bought his first cotton candy machine from Target for $40—a small price in creating a technique that could help in engineering much-needed livers, kidneys, or bones.

To read full story Click Here

Credit NICOLE CARPENTER

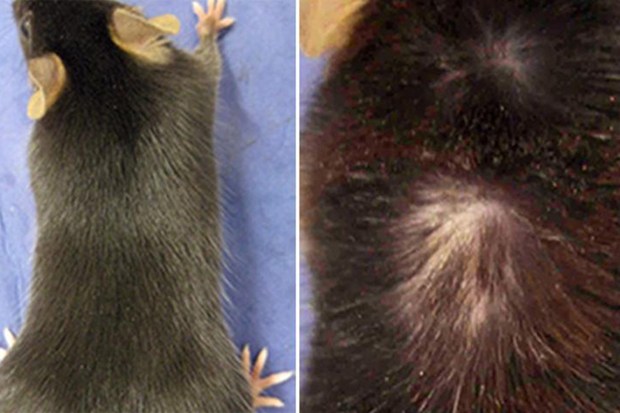

If you were wondering why your hair was looking somewhat less lustrous than in previous years, we finally have an answer for you: it's because your thinning hair is turning into skin.

For the first time, researchers have pinpointed a mechanism that turns age damaged stem cells in hair follicles into skin.

As it happens to more and more stem cells, the hair follicles shrink and eventually disappear -- leaving you hairless. It's the first time such a mechanism has been identified with ageing. Unlike stem cells elsewhere in the body, hair follicle cells regenerate on a cyclical basis -- a growth phase is followed by a dormant phase in which they stop producing hair.

To find out why hair thins, Emi Nishimura and her team at Tokyo Medical and Dental University began looking at follicle stem cell growth cycles in mice. They found that age-related DNA damage triggers the destruction of the protein Collagen 17A1, which in turn triggers the transformation into 'epidermal keratinocytes' -- or skin. When the research was replicated in humans, they found that follicles in people aged over 55 were also smaller, and lower in Collagen 17A1.

"We assume that ageing processes and mechanisms explain the human age-associated hair thinning and hair loss," Nishimura said.

Hair follicle stem cells are now likely to be used as a model for studying more general stem cell behaviour. Researchers are keen to point out that stem cell depletion is unlikely to be the only cause of hair loss, but suggest that Collagen 17A1 could be used as a target for hair loss treatments.

To read full story Click Here

Credit Emily Reynolds

New research attempts to shed light on the most common reasons patients are readmitted post-surgery, and how hospitals can nip the issue in the bud.

In a study recently published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), a team of researchers looked at readmission rates after surgical procedures overall, as well as rates for several specific surgeries. The goal was to determine what sorts of problems caused complications requiring unexpected readmission.

Information was pulled from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. The program tracks the primary reason for a patient’s readmission, which helped researchers figure out whether the subsequent hospital visit was related to the person’s initial condition.

After looking at the data for close to 450 hospitals over a year-long period, researchers found that the number one reason for patients to be readmitted to the hospital after surgery was experiencing a surgical site infection. The second reason: an obstruction or ileus.

To read full story Click Here

Credit Jess White

Newswise — Jan. 22, 2016─A diet rich in fiber may not only protect against diabetes and heart disease, it may reduce the risk of developing lung disease, according to new research published online, ahead of print in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

Analyzing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, researchers report in “The Relationship between Dietary Fiber Intake and Lung Function in NHANES,” that among adults in the top quartile of fiber intake:

• 68.3 percent had normal lung function, compared to 50.1 percent in the bottom quartile. • 14. 8 percent had airway restriction, compared to 29.8 percent in the bottom quartile.In two important breathing tests, those with the highest fiber intake also performed significantly better than those with the lowest intake. Those in the top quartile had a greater lung capacity (FVC) and could exhale more air in one second (FEV1) than those in the lowest quartile.

“Lung disease is an important public health problem, so it’s important to identify modifiable risk factors for prevention,” said lead author Corrine Hanson PhD, RD, an associate professor of medical nutrition at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. “However, beyond smoking very few preventative strategies have been identified. Increasing fiber intake may be a practical and effective way for people to have an impact on their risk of lung disease.”

Researchers reviewed records of 1,921 adults, ages 40 to 79, who participated in NHANES during 2009-2010. Administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NHANES is unique in that it combines interviews with physical examinations.

Fiber consumption was calculated based on the amount of fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grains participants recalled eating. Those whose diets included more than 17.5 grams of fiber a day were in the top quartile and represented the largest number of participants, 571. Those getting less than 10.75 grams of fiber a day were in the lower group and represented the smallest number of participants, 360.

Researchers adjusted for a number of demographic and health factors, including smoking, weight and socioeconomic status, and found an independent association between fiber and lung function. They did not adjust for physical activity, nor did the NHANES data allow them to analyze fiber intake and lung function over time—limitations acknowledged by the authors.

Authors cited previous research that may explain the beneficial effects of fiber they observed. Other studies have shown that fiber reduces inflammation in the body, and the authors noted that inflammation underlies many lung diseases. Other studies have also shown that fiber changes the composition of the gut microbiome, and the authors said this may in turn reduce infections and release natural lung-protective chemicals to the body.

If further studies confirm the findings of this report, Hanson believes that public health campaigns may one day “target diet and fiber as safe and inexpensive ways of preventing lung disease.”

To read the article in full, please visit: http://www.thoracic.org/about/newsroom/press-releases/resources/White-201509-609OC.PDF