News

These daily fluctuations might be subtle, but that doesn't mean they're not happening. By denying or resisting your own transitory nature, you will make yourself utterly miserable.

Most of us do pick up on these changes, whether we're tuned into them every second or every few days. (How many times have you been guilty of muttering, "I feel so fat today" to your best friend?)

Acknowledging them is not only okay, it's normal. Society likes to make women out as "crazy" for having feelings, intuition, and sensitivity. We're judged by standards that were never meant for us, thanks to the patriarchy and our sexually repressed Anglo-Saxon foundation.

Guess what? "Sensitivity" just means we have the gift of being able to pick up on subtle sh*t. If someone calls you "too sensitive," what they really mean "you're making me feel crazy because I can't see the subtle things you see, and I don't like that."

Immediately let go of any narrative you've been clinging to that your emotions or ability to perceive things make you crazy. They don't.

A problem arises, however, when you become deeply attached to only one part of your body's total experience. When your body isn't in the one exact state you are attached to, you might feel shame, anger, or sadness. Maybe you feel like you should look and feel a certain way all the time.

If you desperately crave arrival at an end point, where you can finally rest from the exhausting pursuit of your body's perfection, then it's time to let that go. There is no such end point. The only way you can rest is by letting go of the attachment.

How to do that? By realizing that these fluctuations are a very normal—healthy even—part of existing in a human body. Let's take a look at a handful of changes your body might go through on a daily basis that could trigger attachment anxiety.

On a Thursday you look in the mirror. You've been eating well since Sunday, crushing your workouts, and getting lots of sleep all week. You look at your naked body and think, God, yes! I look awesome. Then you put on something hot and go out to happy hour for margaritas and Mexican food.

You wake up on Friday morning to find a bloated hippopotamus looking back at you in the mirror. If you weighed yourself, you might even be up three to five pounds from the night before.

Now, let's look at the facts here. Did you gain a bunch of fat since yesterday? No, that's impossible. Is it all in your head? No, because as we've established already, you're not a crazy person. (You have a female superpower. You pick up on subtle changes.)

So what caused this overnight change? Water retention. Due to some awesome chemistry between salt, water, carbs, and even alcohol, your body can either be holding a little water or a lot.

Bodybuilders and fitness models manipulate the way their bodies hold water in order to "peak," which just means they get as dehydrated and "dry" as possible for a very temporary appearance of maximum leanness.

The "water pills" and diuretics that are sold over the counter create a similar effect. The results of a dedicated peaking protocol, which have nothing to do with fat, are dramatic. You can go from pretty lean to "holy sh*t, I'm shredded" just by playing with water retention. However, it's extremely temporary, and in many cases, it's also wildly unhealthy.

At some point in your life, you may have accidentally "peaked." In my example above, you might have felt de-puffed on Thursday night thanks to a week of drinking lots of water, sweaty workouts, and eating low-sodium and low-carb home-cooked dinners. By attaching your happiness to this one small part of the experience, of having a body in which you retain very little water, you set yourself up to feel awful the next day when it shifted again.

It's also worth mentioning here that the stress hormone cortisol causes you to hold water in a major way. So if you've been restful, sleeping a lot, and happy all week, your cortisol will be low, and therefore, so will your water-retention levels. This is one of the main reasons for that mysterious "vacation abs" phenomenon, when (despite eating whatever you want and not working out) your body looks inexplicably lean and sexy on vacation. If you hold a lot of water normally due to stress, suddenly being restful and joyful will bring about some fluctuations. Elevation, like traveling by plane, can also cause changes in water retention.

So what to do?

Stop worshipping one half of this cycle and condemning the other. There are certainly some habitual lifestyle factors worth considering and improving here, such as getting more sleep, lowering stress, drinking more water, and eating less processed foods. But water fluctuations are normal. Even someone who is super healthy will notice them from time to time. So find love for the puff.

To read full story click here

Credit JESSI KNEELAND

If you were wondering why your hair was looking somewhat less lustrous than in previous years, we finally have an answer for you: it's because your thinning hair is turning into skin.

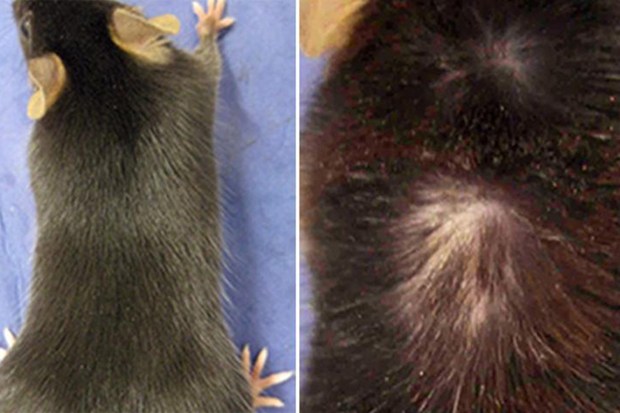

For the first time, researchers have pinpointed a mechanism that turns age damaged stem cells in hair follicles into skin.

As it happens to more and more stem cells, the hair follicles shrink and eventually disappear -- leaving you hairless. It's the first time such a mechanism has been identified with ageing. Unlike stem cells elsewhere in the body, hair follicle cells regenerate on a cyclical basis -- a growth phase is followed by a dormant phase in which they stop producing hair.

To find out why hair thins, Emi Nishimura and her team at Tokyo Medical and Dental University began looking at follicle stem cell growth cycles in mice. They found that age-related DNA damage triggers the destruction of the protein Collagen 17A1, which in turn triggers the transformation into 'epidermal keratinocytes' -- or skin. When the research was replicated in humans, they found that follicles in people aged over 55 were also smaller, and lower in Collagen 17A1.

"We assume that ageing processes and mechanisms explain the human age-associated hair thinning and hair loss," Nishimura said.

Hair follicle stem cells are now likely to be used as a model for studying more general stem cell behaviour. Researchers are keen to point out that stem cell depletion is unlikely to be the only cause of hair loss, but suggest that Collagen 17A1 could be used as a target for hair loss treatments.

To read full story Click Here

Credit Emily Reynolds