News

Newswise —

Unlike its viral cousins hepatitis A and B, hepatitis C virus (HCV) has eluded the development of a vaccine and infected more than 170 million people worldwide. Now, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine report that a novel laboratory tool that lets them find virus mutations faster and more efficiently than ever before has identified a biological mechanism that appears to play a big role in helping HCV evade both the natural immune system and vaccines.

For their study, described March 8 in PLOS Pathogens, the researchers used one of the largest libraries of naturally occurring HCV to rapidly sort out which mutations allow HCV to evade immune responses and found that mutations that occur outside of the viral sites typically targeted by such antibody responses play a major role in the virus' resistance.

"We think those mutations could account for the difficulty of making an effective vaccine," says Justin Bailey, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

All told, the researchers compiled a library of 113 HCV strains from 27 patients with HCV infections followed at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. The researchers then tested each strain of the virus for susceptibility to two potent and commonly used antibodies in vaccine development experiments for HCV, HC33.4 and AR4A.

Because natural HCVs do not thrive in the lab, the researchers first created pseudo-viruses using the contents and capsule of HIV, a virus that grows easily in the lab. Then, by placing surface proteins of each HCV virus onto these pseudoviruses, the researchers were able to efficiently infect human cells with the HCV strains in tissue culture.

One-third of the cells infected with each strain received treatment with HC33.4 antibodies, one-third received treatment with AR4A antibodies and a final third (the control group) received no treatment. The researchers then compared the level of infection in the treated cells against the untreated cells.

The investigators observed that HC33.4 and AR4A neutralized only 88 percent and 85.8 percent of the virus, respectively. "We discovered that there was a lot of naturally occurring resistance, meaning we may need to greatly expand the set of viruses we use to evaluate potential vaccines," says Ramy El-Diwany, a student at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and first author of the study.

The team also found that the effectiveness of the antibodies varied, with some viral strains very inhibited by the antibodies and others hardly affected at all. To find out what was causing the variation, the researchers next tapped into the HCV genomes.

Using a program that compared the genetic sequences of each viral strain, the researchers were able to analyze which mutations conferred resistance to each strain of the virus. They found that despite wide-ranging levels of resistance to HC33.4 and AR4A, the areas that allow these antibodies to bind to the virus barely varied. The HC33.4 binding site mutated at only one location, for example, and the AR4A binding site was the same across all viral strains.

The researchers then expanded their search to the proteins on the surface of HCV. They found that while mutations in the binding site were not associated with resistance, other mutations in the surface proteins away from the binding site correlated with viruses that persisted despite antibody treatment.

"These are the mutations we believe may allow the viruses to avoid being blocked by antibodies altogether. If you think of it like a race, the antibody is trying to bind to the virus before it can enter the cell. We think this mutation may allow the virus to get into the cell before it even encounters the immune system," says Bailey.

HCV is spread from person to person through contact with the blood of an infected person. Some patients are able to fight off the infection naturally, but for 70 to 85 percent of people, the infection becomes chronic.

A new HCV infection is effectively treated with direct-acting antiviral drugs, but the researchers say a preventive vaccine is needed to control what they call an HCV pandemic because as many as 50 percent of people infected are unaware that they carry the virus, putting others at risk of infection. Treatment does not protect those at risk from future infection by HCV. "HCV is very unlikely to be eliminated by treatment alone," says El-Diwany.

Other researchers involved in this study include Valerie Cohen, Madeleine Mankowski, Lisa Wasilewski, Jilian Brady, Anna Snider, William Osburn and Stuart Ray of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and Ben Murrell of the University of California, San Diego.

This research was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Extramural Activities (1K08 AI102761, U19 AI088791), the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R37 DA013806), and the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research (1P30AI094189).

Newswise —

Results of a new study by Johns Hopkins researchers using national data add to evidence that living in inner cities can worsen asthma in poor children. They also document persistent racial/ethnic disparities in asthma.

A report of the study's findings, published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology on March 8, shows that urban living and black race are strong independent risk factors for increased asthma morbidity -- defined as higher rates of asthma-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations -- but urban living does not increase the risk for having asthma.

"Our findings serve as evidence that there are differences between risk factors linked to developing asthma and those linked to making asthma worse if you already have it," says Corinne Keet, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the paper's lead author.

To the researchers' knowledge, few previous studies have been conducted on a national level to determine the effects of inner-city living on both asthma prevalence and severity. While Keet's previous work published in 2015 using a national survey showed that living in an urban area was not a risk factor for having asthma, that study didn't allow for analysis of asthma morbidity.

The research team sought to determine those effects by analyzing information gathered by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on the health care utilization of 16,860,716 children ages 5 to 19 who were enrolled in Medicaid in 2009 and 2010.

The team first narrowed the pool of data to children who had at least one asthma-related outpatient or Emergency Department visit over the two-year period. Based on the county they lived in, these 1,534,820 children were categorized by urbanization status and based on their ZIP code, categorized as living in a poor or not poor neighborhood.

Urbanization status identification took into account locations including urban, suburban, medium metro, and a category that combined smaller metro and rural regions. Inner-city residence was defined as living in an urban county and ZIP code where at least 20 percent of households were below the federal poverty line, defined as an income of less than $22,050 for a family of four in 2009.

The team excluded states that were missing more than 10 percent of data on race/ethnicity, states in which all major race/ethnicity groups were not represented and states that did not have urban areas.

The results for 18 states that met the study's final guidelines showed that children who lived in nonurban areas were 18 to 21 percent less likely to be at risk for hospitalizations, even after accounting for race/ethnicity. The researchers also found that compared to non-Hispanic white children, black children and children of "other" races had 89 and 61 percent, respectively, higher risks of asthma-related hospitalizations.

Unlike other racial/ethnic groups, Hispanic children who live in a nonurban area did not experience reduced risks of emergency room visits or hospitalizations. And contrary to Keet's previous studies, which reported that poverty was protective against asthma prevalence rates for Hispanic children, the team found no similar association for asthma morbidity.

Keet says that among the Medicaid population she studied, 30 percent of asthma-related hospitalizations were likely attributable to socioeconomic, geographic and/or racial/ethnic disparities; 19 percent of hospitalizations were estimated to be attributable to black race/ethnicity; 4 percent were attributable to living in a poor area; and 7 percent were attributable to living in an urban area.

Children who lived in inner-city areas had an overall 40 percent higher risk of asthma-related emergency room visits and 62 percent higher risk of asthma-related hospitalizations. After adjusting for race/ethnicity, risk was lowered to 14 percent and 30 percent higher for emergency room visits and hospitalizations, respectively.

While this study did not look at any specific environmental exposures associated with urbanization, the findings are in keeping with previous work that shows that certain risk factors concentrated in urban areas, such as exposure to mice and cockroach allergens and air pollution, are associated with asthma morbidity.

Keet says the new study affirms her team's earlier finding that asthma rates or prevalence were not affected by residing in inner-city areas, strengthening evidence that risk factors for the cause of asthma are independent of those that worsen it. For example, exposure to pest allergens is associated with increased asthma morbidity but protects high-risk children from developing allergies.

"These results show that despite several decades of research on racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in asthma morbidity, there are still very large differences in rates of emergency room visits and hospitalizations by race and neighborhood characteristics. These findings emphasize that we need to redouble our efforts to find comprehensive solutions to address asthma disparities," concludes Keet.

The study's two main limitations were that not all states could be included because of differences in Medicaid data collection, and that it is possible that some of the differences in emergency room visits and hospitalizations could be related to how patients seek care for asthma, rather than only reflecting underlying disease severity.

BUFFALO, N.Y. —

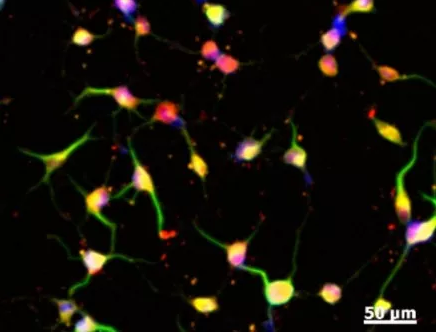

A discovery, several years in the making, by a University at Buffalo research team has proven that adult skin cells can be converted into neural crest cells (a type of stem cell) without any genetic modification, and that these stem cells can yield other cells that are present in the spinal cord and the brain.

The applications could be very significant, from studying genetic diseases in a dish to generating possible regenerative cures from the patient’s own cells.

“It’s actually quite remarkable that it happens,” says Stelios T. Andreadis, PhD, professor and chair of UB’s Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, who recently published a paper on the results in the journal Stem Cells.

The identity of the cells was further confirmed by lineage tracing experiments, where the reprogrammed cells were implanted in chicken embryos and acted just as neural crest cells do.

Stem cells have been derived from adult cells before, but not without adding genes to alter the cells. The new process yields neural crest cells without addition of foreign genetic material. The reprogrammed neural crest cells can become smooth muscle cells, melanocytes, Schwann cells or neurons.

“In medical applications this has tremendous potential because you can always get a skin biopsy,” Andreadis says. “We can grow the cells to large numbers and reprogram them, without genetic modification. So, autologous cells derived from the patient can be used to treat devastating neurogenic diseases that are currently hampered by the lack of easily accessible cell sources.”

The process can also be used to model disease. Skin cells from a person with a genetic disease of the nervous system can be reprogrammed into neural crest cells. These cells will have the disease-causing mutation in their chromosomes, but the genes that cause the mutation are not expressed in the skin. The genes are likely to be expressed when cells differentiate into neural crest lineages, such as neurons or Schwann cells, thereby enabling researchers to study the disease in a dish. This is similar to induced pluripotent stem cells, but without genetic modification or reprograming to the pluripotent state.

The discovery was a gradual process, Andreadis says, as successive experiments kept leading to something new. “It was one step at a time. It was a very challenging task that took almost five years and involved a wide range of expertise and collaborators to bring it to fruition,” Andreadis says. Collaborators include Gabriella Popescu, PhD, professor in the Department of Biochemistry in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB; Song Liu, PhD, vice chair of biostatistics and bioinformatics at Roswell Park Cancer Institute and a research associate professor in biostatistics UB’s School of Public Health and Health Professions; and Marianne Bronner, PhD, professor of biology and biological engineering, California Institute of Technology.

Andreadis credits the persistence of his then-PhD student, Vivek K. Bajpai, for sticking with it.

“He is an excellent and persistent student,” Andreadis says. “Most students would have given up.” Andreadis also credits a seed grant from UB’s office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development’s IMPACT program that enabled part of the work.The work recently received a $1.7 million National Institutes of Health grant to delve into the mechanisms that occur as the cells reprogram, and to employ the cells for treating the Parkinson’s-like symptoms in a mouse model of hypomyelinating disease.“This work has the potential to provide a novel source of abundant, easily accessible and autologous cells for treatment of devastating neurodegenerative diseases. We are excited about this discovery and its potential impact and are grateful to NIH for the opportunity to pursue it further,” Andreadis said.

The research, described in the journal Stem Cells under the title “Reprogramming Postnatal Human Epidermal Keratinocytes Toward Functional Neural Crest Fates,” was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise —

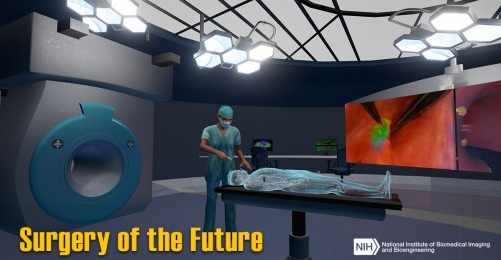

Surgery of the Future is a virtual operating room that showcases government-funded technologies currently being developed to make surgery safer, more effective, and less invasive.

Tremendous strides have been made in surgical outcomes during the past 50 years, thanks in large part to the development of a wide range of biomedical technologies. For example, advances in imaging technologies have made it easier for surgeons to plan surgical approaches so that they avoid cutting through healthy tissue, while robotic technologies have enabled surgeons to operate inside smaller incisions with greater accuracy and precision.

So what novel surgical technologies can we expect in the future? The National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) wants to give you a sneak-peak with their new “Surgery of the Future” interactive experience. Users can click on objects in 3-D virtual operating room to learn about a number of futuristic advances.

For example, there are robots that can stitch tissues by themselves, biomaterials that dissolve or expand once inside the body, and even a tool that can reduce a surgeons’ natural hand tremor while operating.

A video promo of the app and how to download it onto iOS devices and very soon for android devices, is here: https://www.nibib.nih.gov/Surgery-of-Future.

Newswise — ANN ARBOR, MI –

An emergency room visit for an illness or injury may seem like a strange time to try to motivate someone to cut back on using drugs.

But a new study suggests that even a half-hour chat with a trained counselor, or a few minutes using a special tablet computer program with a “virtual therapist”, can turn an emergency room trip into the basis for a long-lasting drop in a person’s use of illegal drugs or misuse of prescription medicines.

The findings, from a carefully designed randomized controlled trial involving 780 people at a Flint, Michigan ER who indicated recent drug use on a health survey, suggest that ER visits might serve as effective ‘teachable moments’ for drug use.

Published in the journal Addiction by a team from the University of Michigan Addiction Center and Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, the study looks at the impact of a drug-related brief intervention based on a technique called motivational interviewing.

The study randomly assigned two-thirds of the participants to an intervention aimed at motivating them to set goals for cutting back on their substance use, on their own or with help. Then, the researchers followed up with all participants three times in the year after their ER visit – including urine tests to check the accuracy of participants’ statements about their drug use.

Those who talked with a therapist, who used the tablet program to guide the discussion, reported significantly fewer days of drug use in the year after the ER visit -- about 21 percent less -- and fewer days on which they used multiple drugs. And even those who didn’t talk with a therapist, but interacted with a virtual therapist on a computer program on their own, had 16 percent fewer days of marijuana use a year later.

Though other studies have cast doubt on the effectiveness of this approach for reducing drug use, study leader Frederic Blow, Ph.D., director of the U-M Addiction Center, says the new findings come from a trial that was carefully planned and conducted, with high follow-up rates.

“Our results show that this approach can work if it’s done well, and that the perception that people won’t change their use based on motivational approaches is nonsense,” says Blow. “The findings especially support engaging computer-based aids that help therapists deliver this brief intervention in a way that tailors it to the individual patient, and works with them to make a plan for reducing their substance use.”

Blow is a professor of psychiatry at the U-M Medical School’s Department of Psychiatry, and a research scientist at the Center for Clinical Management Research at the Ann Arbor Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System.

Blow and his colleagues worked with a technology firm to create the tablet interface called HealthiER You, using a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. They recruited participants in the ER of Hurley Medical Center, which partners with U-M’s academic medical center Michigan Medicine to provide emergency care.

Most of the study participants were low-income adults their 30s – a demographic group that has high rates of substance use, and may be less likely to access other healthcare services outside the ER. The study did not include people with certain psychiatric conditions or those seeking care for suicidal thinking or sexual assault.

“An ER visit is a time that may prompt people to think about their lives, and be more receptive to thinking about their drug use,” says Blow. “This is not about going cold turkey, but about setting goals to reduce or stop use for health reasons.”

He notes that previous research has already shown that motivational interviewing in the ER can help people reduce their alcohol use, and that previous studies to use it for substance use have yielded mixed or negative results.

But the new study used random selection to find participants across all 24 hours of the day, and excluded people who inject drugs. It also tailored the program interface to the answers that participants gave on questionnaires. Screen shots of the program are available in the paper.

The control group also showed a modest drop in drug use, most likely because they were asked about their use of drugs in the ER and at each follow-up. This could also be true of the intervention groups. Nonetheless, there was a significant drop in drug use by members of the groups that received the active interventions, compared to the control group.

Blow and his colleagues hope that further research will put their results to the test. Because their study showed that follow-up interventions by therapists three months after the ER visit did not have a measurable effect, they also hope to study the impact of peer support, text messages, and other tools in the post-ER timeframe.

“We believe interventions like these can work in a range of populations, if we deliver them in a motivational way that figures out the best options for each person and supports them with electronic or personal contact that forms a real connection over time,” says Blow.

In addition to Blow and senior author Kristen L. Barry, Ph.D., the study’s authors are U-M’s Maureen A. Walton, M.P.H., Ph.D., Amy S.B. Bohnert, Ph.D., Rosalinda V. Ignacio, M.S., Stephen Chermack, Ph.D., Mark Ilgen, Ph.D.; Rebecca M. Cunningham, M.D. (from Emergency Medicine), and Brenda M. Booth, Ph.D. of the University of Arkansas for Medical Science and VA Center for Mental Healthcare Outcomes and Research.

Drs. Blow, Barry, Walton, Bohnert, Cunningham, and Ilgen are members of the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation (IHPI). All but Barry are also members of the U-M Injury Center, which Cunningham directs. Blow, Bohnert, and Ilgen are members of the VA Center for Clinical Management Research. The study was funded by grant DA026029.

Reference: Addiction, Early View, DOI: 10.1111/add.13773 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.13773/pdf

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise — BIRMINGHAM, Ala. –

Failure of hormone deprivation therapy, which is used to slow prostate cancer in patients, leads to castration-resistant prostate cancer, a lethal form of advanced disease with limited treatment options.

University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers have discovered that endostatin, a naturally occurring protein in humans, can significantly decrease proliferation of castration-resistant prostate cells in culture, and in a recent paper in The FASEB Journal, they describe the physiological pathways and signaling evoked by endostatin. This endostatin effect is now being tested in a preclinical xenograft animal model of castration-resistant prostate cancer.

“We hope we can delay the onset of castration-resistant disease,” said Selvarangan Ponnazhagen, Ph.D., a UAB professor in the UAB Department of Pathology who holds an Endowed Professorship in Experimental Cancer Therapeutics at UAB.

The medical treatment that deprives prostate cancer cells of androgen hormones through anti-hormone therapy creates oxidative stress in those cancer cells. This oxidative stress is associated with reactivated signaling by the androgen receptor in the cells, causing resistance to the anti-hormone therapy.

The UAB researchers, led by Ponnazhagen and first author Joo Hyoung Lee, Ph.D., hypothesized that the oxidative stress might be triggered upstream of the androgen receptor, with the glucocorticoid receptor as the stress-inducer. If so, endostatin might interact with the glucocorticoid receptor to remove the oxidative stress and reduce that pro-tumorigenic function in the cancer cells, thereby preventing or delaying the onset of castration-resistant disease.

They found that endostatin did target the androgen and glucocorticoid receptors through reciprocal regulation that affected downstream pro-oxidant signaling mechanisms. The effect of endostatin treatment, possibly mediated through direct interaction of endostatin with both androgen receptor and glucocorticoid receptor, downregulated both the steroid hormone receptor levels and led to physiological changes that removed oxidative stress from the cancer cells.

Treatment with endostatin resulted in a significant up-regulation of the major cellular machinery to scavenge destructive reactive-oxygen-species, including manganese superoxide dismutase, the glutathione system and the biliverdin/bilirubin redox cycle. Increased levels of reduced glutathione, a major internal antioxidant molecule, was accompanied by increased glucose uptake as the endostatin-treated cancer cells appeared to shift their metabolism to the pentose phosphate pathway. This pathway uses glucose to maintain the antioxidant system, which includes NAD/NADP production and glutathione.

“Our study suggests that the potential therapeutic application of endostatin may include combination with the frontline androgen-deprivation therapy that targets prostate cancer at early stages,” the researchers wrote. “Based on the known anti-angiogenic properties of endostatin and on more interesting evidence that human prostate endothelial cells also express androgen receptor, the application of endostatin in combination therapies could synergize tumoristatic and tumoricidal effects with minimal resistance.”

Besides Ponnazhagen and Lee, authors of the paper, “Endostatin inhibits androgen-independent prostate cancer growth by suppressing nuclear receptor-mediated oxidative stress,” are Minsung Kang and W. Timothy Garvey, UAB Department of Nutrition Sciences; Hong Wang and Victor M. Darley-Usmar, UAB Department of Pathology; Gurudatta Naik and Guru Sonpavde, UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center; and James A. Mobley, UAB Department of Surgery. Garvey also serves in the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and Lee is a research associate in pathology.

Newswise — BLOOMINGTON, Ind. --

A study by Indiana University researchers has identified 24 compounds -- including caffeine -- with the potential to boost an enzyme in the brain shown to protect against dementia.

The protective effect of the enzyme, called NMNAT2, was discovered last year through research conducted at IU Bloomington. The new study appears today in the journal Scientific Reports.

"This work could help advance efforts to develop drugs that increase levels of this enzyme in the brain, creating a chemical 'blockade' against the debilitating effects of neurodegenerative disorders," said Hui-Chen Lu, who led the study. Lu is a Gill Professor in the Linda and Jack Gill Center for Biomolecular Science and the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, a part of the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences.

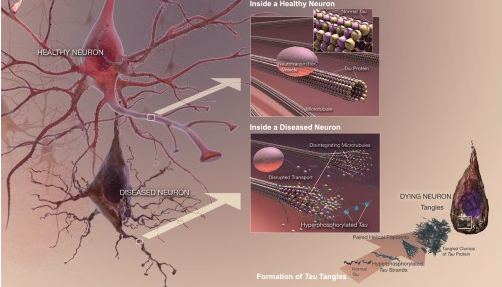

Previously, Lu and colleagues found that NMNAT2 plays two roles in the brain: a protective function to guard neurons from stress and a “chaperone function” to combat misfolded proteins called tau, which accumulate in the brain as "plaques" due to aging. The study was the first to reveal the "chaperone function" in the enzyme.

Misfolded proteins have been linked to neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases, as well as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease. Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of these disorders, affects over 5.4 million Americans, with numbers expected to rise as populations age.

To identify substances with the potential to affect the production of the NMNAT2 enzyme in the brain, Lu’s team screened over 1,280 compounds, including existing drugs, using a method developed in her lab. A total of 24 compounds were identified as having potential to increase the production of NMNAT2 in the brain.

One of the substances shown to increase production of the enzyme was caffeine, which also has been shown to improve memory function in mice genetically modified to produce high levels of misfolded tau proteins.

Lu's earlier research found that mice altered to produce misfolded tau also produced lower levels of NMNAT2.

To confirm the effect of caffeine, IU researchers administered caffeine to mice modified to produce lower levels of NMNAT2. As a result, the mice began to produce the same levels of the enzyme as normal mice.

Another compound found to strongly boost NMNAT2 production in the brain was rolipram, an "orphaned drug" whose development as an antidepressant was discontinued in the mid-1990s. The compound remains of interest to brain researchers due to several other studies also showing evidence it could reduce the impact of tangled proteins in the brain.

Other compounds shown by the study to increase the production of NMNAT2 in the brain -- although not as strongly as caffeine or rolipram -- were ziprasidone, cantharidin, wortmannin and retinoic acid. The effect of retinoic acid could be significant since the compound derives from vitamin A, Lu said.

An additional 13 compounds were identified as having potential to lower the production of NMNAT2. Lu said these compounds are also important because understanding their role in the body could lead to new insights into how they may contribute to dementia.

"Increasing our knowledge about the pathways in the brain that appear to naturally cause the decline of this necessary protein is equally as important as identifying compounds that could play a role in future treatment of these debilitating mental disorders," she said.

Other researchers on the study were assistant research scientist Yousuf O. Ali and graduate student Gillian Bradley, both of the Linda and Jack Gill Center for Biomolecular Science at IU Bloomington. Ali and Lu are co-corresponding authors on the paper.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Belfer Family Foundation.

SEE ORIGINAL STUDY

Newswise —

T cells, the managers of our immune systems, spend their days shaking hands with another type of cell that presents small pieces of protein from pathogens or cancerous cells to the T cell. But each T cell is programmed to recognize just a few protein pieces, known as antigens, meaning years can go by without the T cell, or its descendants, recognizing an antigen.

When the T cell does recognize an antigen, it gives the cell presenting the antigen a “hug,” so to speak, instead of a handshake. This initial interaction causes the T cell to search nearby to find other cells that are presenting the same antigen to give them “hugs” as well.

In a study published today in Science Signaling, UCLA researchers have discovered that after the initial hug, T cells become more gregarious, giving something more like a bear hug to any cell presenting its antigen. These larger hugs help to activate the T cell, equipping it to go out into the body and coordinate multi-cellular attacks to fight infections or cancers.

The UCLA team learned that how stiff or soft T cells are controls their response — the cells react slowly when they are stiff and trigger easily when they are soft.

“T cells are like the shy person at the office holiday party who acts stiff until they loosen up a bit and then are all over the dance floor,” said Dr. Manish Butte, associate professor of pediatrics and microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the study’s senior author.

Butte and his colleagues pioneered an approach using an instrument called an atomic-force microscope to make real-time observations about what excites T cells at the nanoscale. Once they learned that T cells soften after activation, the UCLA team identified the biochemical pathway that controls the cell’s stiffness. They then identified drugs that can help the T cells either elicit or subdue a response. The finding provides scientists with a new capability to manipulate the immune system, Butte said.

Diseases arise in people and animals when T cells attack the body’s other cells, or when they fail to signal attacks against cancer cells or infectious pathogens.

“Until now, we had a limited understanding of what controls T cell activation,” said Butte, who is chief of pediatric allergy and immunology at Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA and a member of the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. “We wanted to identify how to both encourage and speed up T cell activation for fighting infections and cancers and to disrupt it in order to prevent immune disease. Now that we understand the precise steps taking place, our findings suggest that altering T cell stiffness with drugs could one day help us thwart diseases where T cells are too active or not active enough.”

Butte and colleagues are beginning to apply these findings — in a study funded by the National Institutes of Health — to diminish the role T cells play in triggering Type 1 diabetes.

“We can’t talk about precision medicine and still use a sledgehammer to treat disease,” Butte said. “By exploiting the mechanism we discovered to soften T cells, we could accelerate vaccine responses so a patient won’t need multiple boosters and months of waiting to get full immunity. Or we could stiffen up T cells to prevent the body from rejecting transplanted organs.”

Grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the Stanford Child Health Research Institute, the Morgridge Family Foundation and the National Science Foundation supported the research.

Newswise — DALLAS –

Could lung cancer be hiding in kidney cancer patients? Researchers with the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Kidney Cancer Program studied patients with metastatic kidney cancer to the lungs and found that 3.5 percent of the group had a primary lung cancer tumor that had gone undiagnosed. This distinction can affect treatment choices and rates of survival.

“Kidney cancer spreads primarily to the lungs making the detection of a primary lung cancer difficult. Lung cancer is typically more aggressive than kidney cancer. Undetected, lung cancer may spread and eventually kill the patient,” said Dr. James Brugarolas, Director of the Kidney Cancer Program and Associate Professor of Internal Medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Mel Moffitt, an Army veteran who survived serving in Vietnam, is among those now fighting both lung cancer and kidney cancer.

Mr. Moffitt, 70, was initially diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2008, leading to removal of one of his kidneys. By 2012, the cancer had spread to his lungs and lymph nodes. Before coming to UT Southwestern, he had been told he had less than a year to live. In 2015, a new primary tumor was found in his lung.

“It was like we turned around, and the cancer said ‘By the way, I’m over here too,’” said his wife of 47 years, Kennon Moffitt, whom he met at the officer’s club in El Paso before shipping off to Vietnam.

“I will keep fighting,” pledged Mr. Moffitt, who has been through molecularly targeted drug therapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, and is combating his latest lung and kidney cancer diagnosis with immunotherapy and chemotherapy treatment.

Still, he said, he is grateful to have survived so many years since his initial diagnosis, years that included the birth of his three grandchildren, now ages 8, 6 and 4, and the chance to restore a 1969 red Corvette, which the couple plans to drive in a Fourth of July parade this summer.

Watch Mr. Moffitt’s story.

Nearly 400,000 Americans are now living with a diagnosis of kidney cancer and more than 60,000 people are expected to be diagnosed with kidney cancer this year, according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Five-year survival rate averages range from more than 80 percent for stage 1, when cancer is contained in the kidney, to about 53 percent for stage 3, when it has spread beyond the kidney, to just 8 percent for stage 4, when the cancer spreads to more distant parts of the body or other organs.

Texas has the fifth-highest rate of this cancer in the U.S. and it is the fourth most common cancer treated at the Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, where survival rates for patients with stage 4 kidney cancer are double national benchmarks, noted Dr. Brugarolas, a Virginia Murchison Linthicum Scholar in Medical Research at UT Southwestern.

In this retrospective study of 151 patients at the Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, investigators identified 85 people who had kidney cancer metastasized to the lungs, and three who had a primary lung cancer. Investigators found only four previous cases described in the literature, leading them to suspect the incidence of lung cancers in kidney cancer patients may be underreported.

Because UT Southwestern is a tertiary care referral center, investigators noted that rates could be different in the general population. Up to 6 percent of patients with metastatic kidney cancer also may have a lung cancer, investigators noted in the study, published in Clinical Genitourinary Cancer.

“Our report raises an important flag for medical oncologists and radiologists to be on the lookout for a hidden lung cancer,” said Dr. Brugarolas.

The study was supported by a SPORE (Specialized Program of Research Excellence) award from the NCI, only the second such award for kidney cancer in the nation. The SPORE investigators are working to better understand how kidney cancer develops and spreads, as well as to develop new therapies targeting adult and pediatric kidney cancer. UT Southwestern also leads a 20-year, multi-institutional SPORE grant in lung cancer that is the largest thoracic oncology effort in the U.S.

UT Southwestern researchers involved in the current study included Dr. Ivan Pedrosa, Chief of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Associate Professor of Radiology and of the Advanced Imaging Research Center, and a Co-Leader of the Kidney Cancer Program, who holds the Jack Reynolds, M.D., Chair in Radiology; Dr. Payal Kapur, Associate Professor of Pathology and Urology; and Dr. Isaac Bowman, a hematology-oncology fellow, who is first author on the study.

UT Southwestern’s Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center is the only NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in North Texas and one of just 47 NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers in the nation. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center includes 13 major cancer care programs, and its education and training programs support and develop the next generation of cancer researchers and clinicians. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center is among only 30 U.S. cancer research centers to be designated by the NCI as a National Clinical Trials Network Lead Academic Participating Site.

About UT Southwestern Medical Center

UT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution’s faculty includes many distinguished members, including six who have been awarded Nobel Prizes since 1985. The faculty of almost 2,800 is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide medical care in about 80 specialties to more than 100,000 hospitalized patients and oversee approximately 2.2 million outpatient visits a year.

###

Newswise — Anaheim, CA.

HumanN is pleased to announce the launching of Protein40®, a powerful functional foods supplement that delivers three high quality proteins – in one convenient shake for seven full hours of muscle and bone support during the Natural Products Expo West trade show.

HumanN has partnered with Dr. John Ivy, Ph.D., one of the world’s renowned experts in protein timing, nutrition, and exercise performance to create Protein40. Dr. Ivy is the bestselling author of Nutrient Timing: The Future of Sports Nutrition, and serves as the Executive Director of Sports Nutrition Research for HumanN, leading its science team in developing this groundbreaking product for anyone over the age of 40.

“Most people over the age of 35 do not realize that essential hormones associated with a reduction in strength, power and speed of movement to peak exercise begin to naturally decline,” Dr. Ivy shares. “By age 40, you need twice as much protein to simply maintain existing muscle mass, especially as your body’s ability to synthesize protein drops. Most notably, Protein40 has been formulated to help the body aid in muscle recovery and support bone mass.”

Protein40 delivers 20 grams of premium proteins (Whey Protein Isolate, Calcium Caseinate, Micellar Casein) that are digested at different rates for seven continuous hours of support to help address any protein gaps in diet and lifestyle.

These proteins are then combined with essential nutrients to maximize and prolong protein synthesis, including 4g of leucine, a branch amino acid that enhances protein synthesis. Protein40 also provides 50 percent of the recommended daily allowance for magnesium and 30 percent of calcium.

Available in a chocolate flavor, Protein40 features a low glycemic index, contains no artificial sweeteners of flavors, and has only 140 calories per serving

“The biggest mistake I see those seeking [to build] muscle make,” according to Registered Dietician Mari-Etta Parrish, “is to disregard their need to trigger insulin in order to build muscle. In other words, they mistakenly prioritize only protein… and don't realize that a certain amount of sugar or carbohydrate is also necessary to really optimize the muscle maintenance or building process. Not only does [Protein40] contain a balanced combination of highly bio-available proteins, it includes necessary carbohydrate and helpful minerals.”

“We developed Protein40 based on well-established scientific principal to provide an optimal blend of proteins for enhanced muscle and bone performance and recovery,” Dr. Ivy adds.

“Whey isolate is a quickly absorbed fast acting protein. It stimulates muscle protein synthesis within 30 minutes of consumption. Micellar casein is slowly digested and the absorption of its component amino acids is slow. While protein synthesis is slow to respond to micellar casein, its effect is prolonged. It is also the only protein that has been shown to help reduce muscle protein breakdown as well as stimulate muscle protein synthesis. Calcium caseinate’s digestion rate is slower than whey isolate, but faster than micellar casein, and therefore its effect on protein synthesis is intermediate to whey isolate and micellar casein. In addition, calcium caseinate provides calcium for bone health.

The amount of protein is important. HumanN Protein40 provides 20 grams of protein per serving, which is enriched with an additional 2 grams of the branched chain amino acid, L-leucine. Because of the quality of protein used, there are 11.0 g of essential amino acids in each serving and 4.0 g of L-leucine. The ability of a protein supplement to stimulate protein synthesis is closely related to the amount of L-leucine and essential amino acids delivered in the supplement. L-leucine is the key activator of protein synthesis, while the other essential amino acids facilitates the activity of L-leucine. This level of L-leucine and essential amino acids has been found to maximally stimulate muscle protein synthesis.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Ivy is available for interviews upon request. HumanN is exhibiting and conducting product sampling at Expo West in booth 1972.

Dr. John Ivy is the Teresa Lozano Long Endowed Chair Emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin. He received his Ph.D. in Exercise Physiology from the University of Maryland, and trained in physiology and metabolism at Washington University School of Medicine as an NIH Post-Doctoral Fellow. He served on the faculty at the University of Texas for 31 years and as Chair of the Department of Kinesiology and Health Education for 13 years.

Formerly Neogenis Laboratories, HumanN is the only company in the world licensed to use this patented Nitric Oxide platform technology. Powered by a blue ribbon panel Scientific Advisory Board that includes Dr. Nathan Bryan and Dr. John Ivy, HumanN believes in helping every human reach their full potential across every phase of life. As a University of Texas Austin technology portfolio company, HumanN upholds extremely high standards in the production of its line of functional foods and supplements, including conducting human clinical trials to support the safety and efficacy of its products. In 2016, HumanN was named to the Inc. 5000 List for the second straight year, and has been featured in The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, Men’s Journal, and more.